Oy Yew is a children's novel set in another world. It's not a world of magic or dragons or aliens, but a world much like ours around the time of Charles Dickens' stories.

Oy is a tiny boy who grows up sustaining himself on crumbs and the smells of food. He's mostly unnoticed until one day someone does spot him. Then, he is quickly caught and forced into servitude, first in a factory, then in a country mansion. His comrades in slavery are other waifs, children from Poria who arrived on the shores of Affland as boat people on tiny rafts, sent across the sea by desperate parents during a famine.

Oy is the smallest waif, the quietest waif, the one who listens and offers nothing but kindness and intuition to those around him. His presence gradually improves the lives of the other waifs, but it also brings with it an intuition that something is wrong. How come there have been more accidents than usual lately, always befalling the waifs about to be freed? What secrets lurk in the sinister Bone Room? And why is Master Jep, a bone collector, suddenly so interested in Oy's thumbs?

Oy Yew is a fantastically atmospheric novel. It reminded me of Otfried Preussler's Krabat, and of Michael Ende's Momo. (Oy is quite similar to Momo in many ways). Or, in more British terms, of Alan Garner's scary children's novels - except that the atmosphere in Oy Yew is richer, the story more lovingly told. There is a tenderness in Oy Yew where Alan Garner goes for grand drama, and that tenderness makes it a more beautiful story. Basically, it's a superior novel to The Owl Service and The Weirdstone of Brisingamen.

It's not flawless: at times, the text moves too fast, in a disorienting way. Some of that disorientation happens early on, which could discourage some readers. I don't know whether the author was trying to create an atmosphere of hectic movement, or whether she saw the story in her mind and left out some words that might have helped me as a reader to follow it. All I know is that there were quite a few times when I was a little bewildered over who was there, who was who, and what was going on. I imagine child readers are likely to get confused, too. Those moments of bewilderment are literally the only flaw, and it's very much worth persevering if the text befuddles you momentarily.

The prose is beautiful, the story is filled with atmosphere, creepiness, tension, kindness and joy. The waifs are lovely and the characters around them include quite a few memorable personalities. Even as an adult reader, I was on the edge of my seat at many points, and I felt the peril in the story was real.

To my mind, this is one of the finest children's novels ever written. It's so good that I consider myself an instant fan of the author and immediately ordered the sequel.

Rating: 5/5

Showing posts with label Victoriana. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Victoriana. Show all posts

Tuesday, 23 October 2018

Monday, 22 October 2018

Review: The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle by Stuart Turton

The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle is a high concept crime novel. Its one-sentence pitch is "Groundhog Day crossed with Agatha Christie".

Our hero wakes up without memories, with a single word on his lips: "Anna". He's in a forest and witnesses a young woman being chased by a villain. He hears screams and a gunshot. And then someone pursues him, gives him a compass, whispers a word in his ear, and allows him to flee to the nearby country mansion Blackheath.

In Blackheath, he finds people who know him, but his memories stay out of reach. All he recalls is the violence he witnessed that morning. The day progresses with an unsettling feeling that there are dark secrets lurking in the house and the people who are gathered here. However, he manages to make one single friend, Evelyn Hardcastle, who sees possibility and potential in his blank state. A promise of renewal, a new start, a chance to become a better man (for there are unpleasant rumours about his profession...)

The next morning, our hero awakes again, but in a different body, reliving the same day, looking at it through different eyes. It is the day of Evelyn Hardcastle's murder, and our hero's task is to solve it.

Seven Deaths is a novel that manages to build up intrigue and tension relatively gradually. If it weren't for the title, a reader might find the first chapters a bit slow, confusing and frustrating. (We don't even find out that Evelyn Hardcastle dies until he has gone through the day several times!) Fortunately, the title tells us the grand drama that the narrator does not know, and therefore adds tension even in moments when the narrator is bumbling along gormlessly.

Each body he inhabits is different, and each body comes with different emotional patterns, instincts, and physical limitations. After the first day, our narrator is in a constant battle between his own mind and the habits of the person he occupies. Short-tempered people, calculating people, flighty people, sometimes his hands do things before his conscious mind notices them. It's a very interesting idea, and I think in the hands of a virtuoso, it could have been gobsmackingly brilliant to read. Stuart Turton is a good writer, but not a prodigy, so he tackles this deftly but not very immersively or subtly by having our narrator tell us about his struggles. The same goes for the rest of the book: it is written well, but the genius is in the concept, not so much in the execution. Characters may have secrets, but they don't tend to have much complexity. The basic crime story has peril, but is thin on authenticity. The end result is a book that is immensely readable and good fun, but which feels like you can glimpse a hint of a magnificent could-have-been through the text that is. A good novel that feels like it might have been great.

Definitely worth a read.

Rating: 4/5

Our hero wakes up without memories, with a single word on his lips: "Anna". He's in a forest and witnesses a young woman being chased by a villain. He hears screams and a gunshot. And then someone pursues him, gives him a compass, whispers a word in his ear, and allows him to flee to the nearby country mansion Blackheath.

In Blackheath, he finds people who know him, but his memories stay out of reach. All he recalls is the violence he witnessed that morning. The day progresses with an unsettling feeling that there are dark secrets lurking in the house and the people who are gathered here. However, he manages to make one single friend, Evelyn Hardcastle, who sees possibility and potential in his blank state. A promise of renewal, a new start, a chance to become a better man (for there are unpleasant rumours about his profession...)

The next morning, our hero awakes again, but in a different body, reliving the same day, looking at it through different eyes. It is the day of Evelyn Hardcastle's murder, and our hero's task is to solve it.

Seven Deaths is a novel that manages to build up intrigue and tension relatively gradually. If it weren't for the title, a reader might find the first chapters a bit slow, confusing and frustrating. (We don't even find out that Evelyn Hardcastle dies until he has gone through the day several times!) Fortunately, the title tells us the grand drama that the narrator does not know, and therefore adds tension even in moments when the narrator is bumbling along gormlessly.

Each body he inhabits is different, and each body comes with different emotional patterns, instincts, and physical limitations. After the first day, our narrator is in a constant battle between his own mind and the habits of the person he occupies. Short-tempered people, calculating people, flighty people, sometimes his hands do things before his conscious mind notices them. It's a very interesting idea, and I think in the hands of a virtuoso, it could have been gobsmackingly brilliant to read. Stuart Turton is a good writer, but not a prodigy, so he tackles this deftly but not very immersively or subtly by having our narrator tell us about his struggles. The same goes for the rest of the book: it is written well, but the genius is in the concept, not so much in the execution. Characters may have secrets, but they don't tend to have much complexity. The basic crime story has peril, but is thin on authenticity. The end result is a book that is immensely readable and good fun, but which feels like you can glimpse a hint of a magnificent could-have-been through the text that is. A good novel that feels like it might have been great.

Definitely worth a read.

Rating: 4/5

Monday, 29 May 2017

Review: River of Teeth by Sarah Gailey

River of Teeth is a novella that is completely irresistible. Here's the back cover blurb:

An alternative Western, full of hippos and cowboys riding on hippos, herding hippos, ranching hippos? As alternative histories go, that has surely got to be one of the most unashamedly fun premises ever conceived, made all the more delicious by the fact that it is based on a real historic plan which never quite got carried out..

And as far as the hippos go, the novella doesn't disappoint one bit. Ruby, Abigail, Rosa and Betsy (the hippos) are show stealers: the human cast of the story are, to be honest, not half as interesting as their mounts.

Aside from the novelty factor, River of Teeth is a fast moving story of revenge and a greatcaper totally-above-board operation, featuring an evil robber baron as villain, as well as a motley crew of Western archetypes: an ex-rancher, a gun-for-hire, an assassin, a technical (explosives & poisons) expert, a pickpocket con woman...

This being 2017, post Hugo-gamergate-alt-right-social-justice-warrior kerfuffle, the cast is ethnically and sexually hyper-diverse to the point of very ham-fisted pandering to (certain) audiences' demands. It's mildly distracting, until one of the plot points is the fact that the only white male of the group has become unavailable for a task that only a white male with a moustache could accomplish, putting the quest at risk. That particular obstacle, and its resolution, are more full of plotholes than an Emmental cheese.

As a matter of fact, the story as a whole is quite full of holes and discontinuities: it could have used some editorial browbeating into something that has convincing internal logic. For a novella, the cast of characters is quite big, so the story spends 40% of its length on putting the gang together. Some characters turn out to not have very many tasks to accomplish within the gang, fulfilling narrative purposes rather than fitting the mission. Internal logic, it turns out, only mattered to the author when it comes to the hippos (the appendix contains a detailed history of this alternative America and its hippos). For the main plot, not so much.

Despite the OTT diversity pandering and the very loose attitude towards internal logic, River of Teeth is rollicking fun. Ultimately, this is a Western filled with hippos, and it moves fast enough and has hippos enough to make its narrative sins more than forgivable.

Great fun!

Rating: 4/5

"In the early 20th Century, the United States government concocted a plan to import hippopotamuses into the marshlands of Louisiana to be bred and slaughtered as an alternative meat source. This is true.

Other true things about hippos: they are savage, they are fast, and their jaws can snap a man in two.

This was a terrible plan.

Contained within this volume is an 1890s America that might have been: a bayou overrun by feral hippos and mercenary hippo wranglers from around the globe. It is the story of Winslow Houndstooth and his crew. It is the story of their fortunes. It is the story of his revenge."

An alternative Western, full of hippos and cowboys riding on hippos, herding hippos, ranching hippos? As alternative histories go, that has surely got to be one of the most unashamedly fun premises ever conceived, made all the more delicious by the fact that it is based on a real historic plan which never quite got carried out..

And as far as the hippos go, the novella doesn't disappoint one bit. Ruby, Abigail, Rosa and Betsy (the hippos) are show stealers: the human cast of the story are, to be honest, not half as interesting as their mounts.

Aside from the novelty factor, River of Teeth is a fast moving story of revenge and a great

This being 2017, post Hugo-gamergate-alt-right-social-justice-warrior kerfuffle, the cast is ethnically and sexually hyper-diverse to the point of very ham-fisted pandering to (certain) audiences' demands. It's mildly distracting, until one of the plot points is the fact that the only white male of the group has become unavailable for a task that only a white male with a moustache could accomplish, putting the quest at risk. That particular obstacle, and its resolution, are more full of plotholes than an Emmental cheese.

As a matter of fact, the story as a whole is quite full of holes and discontinuities: it could have used some editorial browbeating into something that has convincing internal logic. For a novella, the cast of characters is quite big, so the story spends 40% of its length on putting the gang together. Some characters turn out to not have very many tasks to accomplish within the gang, fulfilling narrative purposes rather than fitting the mission. Internal logic, it turns out, only mattered to the author when it comes to the hippos (the appendix contains a detailed history of this alternative America and its hippos). For the main plot, not so much.

Despite the OTT diversity pandering and the very loose attitude towards internal logic, River of Teeth is rollicking fun. Ultimately, this is a Western filled with hippos, and it moves fast enough and has hippos enough to make its narrative sins more than forgivable.

Great fun!

Rating: 4/5

Monday, 18 April 2016

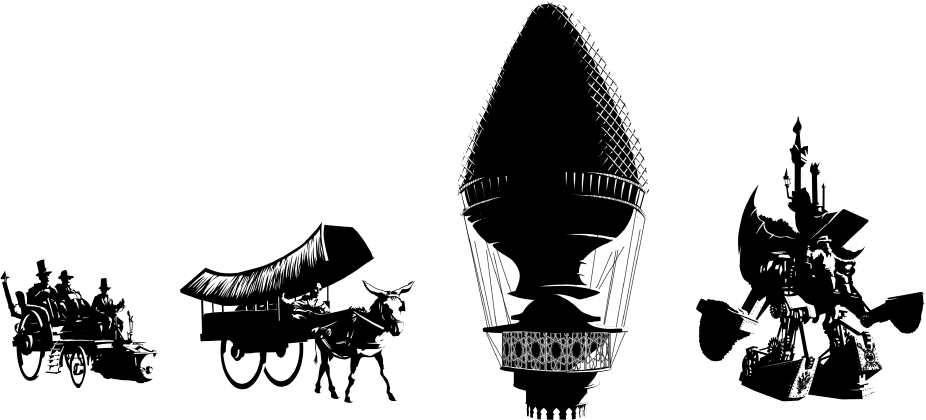

The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage by Sydney Padua

The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage: The (Mostly) True Story of the First Computer is a beautifully produced book. It's hard to describe it: not quite graphic novel, but more than a collection of sketches and comics. Not quite biography, but neither is it just a cartoon fantasy.

I first heard of the comic through watching Calculating Ada on BBC iPlayer: Sydney Padua is one of the people briefly interviewed for the programme, and some of her art is shown. Those brief glimpses of cartoon Ada resonated with me immediately, so when I saw the book in Waterstones, I didn't think twice before buying it, even though I had no idea what the comic itself is actually like.

As such, the introduction was almost a surprise: Sydney Padua was originally asked for a comic showing the real history of Lovelace and Babbage's work. When she didn't like the downbeat ending of real events, she added a final uplifting panel about a pocket (alternative) universe filled with adventures and crime fighting - and people really wanted her to continue that story. The outcome is this book, a hypothetical imagination of what the story would be like if it were to continue as a comic adventure. (Also, the 2D Goggles website)

Like many comics that started on the internet, it doesn't have a continuous story arc, but is a collection of fairly standalone flights of fancy. Where it differs from regular web comics is in its basis, which is always at least inspired by historic quotes and facts, and in its habit of quoting primary sources. Clearly, a lot of research and love has gone into the book. Affection for the characters veritably oozes off the page, while the multiple footnotes per page explain every reference, allusion or detail. Each episode is followed by additional endnotes, which add to the detail from the footnotes, and the book has a further set of appendices on top of that.

The reading experience is quite unusual: almost every line of dialogue and every joke is explained in footnotes. As a German-born man, I principally approve of the explaining of jokes, of course, but it does interrupt the flow of the comic a little. It feels more like getting lost and absorbed in Wikipedia, following one intriguing link after another, with a sense of continuous fascination, than it feels like reading a story.

I guess the book is written for a very specific audience: geeks. Ada Lovelace is, after all, one of the iconic heroes worshipped by 21st century geeks, along Nikola Tesla and other under-appreciated geniuses. This book is not (just) aiming for comedy and entertainment, it wants to get people excited about scientific research and historical figures and events. It wants to educate, and it wants to share the author's fascination and celebrate mankind's capacity for enthusiasm (geekery) itself.

I adored the art / style and loved the enthusiasm. I enjoyed the episodes and the quirky ideas. I appreciated the footnotes and endnotes (unlike other books which have more general knowledge about a topic and sprinkle hidden references that only the cognoscenti can appreciate, Lovelace and Babbage is entirely inclusive of the ignorant, and provides the knowledge to understand each reference), and I think that this book honours Lovelace, Babbage and their contemporaries with clear affection and respect. I loved the whimsiest episodes and ideas the most and couldn't get enough of those.

At times, the book was a little too clever for my taste - I would have loved for Lovelace and Babbage to have a few quirky, whimsical adventures that would have been less bothered with edutainment and more purely narrative-focused. The plot always took last place in the author's priority list, with history, facts, quotes, jokes and whimsy all being more important. Much as I enjoyed the book, I would have liked a little more plot (both inside episodes and between episodes).

Still, if you like steampunk, Victoriana, history, geek culture, comic books, postmodern storytelling and/or a cute aesthetic, then The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage is well worth your time.

Rating: 4/5

I first heard of the comic through watching Calculating Ada on BBC iPlayer: Sydney Padua is one of the people briefly interviewed for the programme, and some of her art is shown. Those brief glimpses of cartoon Ada resonated with me immediately, so when I saw the book in Waterstones, I didn't think twice before buying it, even though I had no idea what the comic itself is actually like.

As such, the introduction was almost a surprise: Sydney Padua was originally asked for a comic showing the real history of Lovelace and Babbage's work. When she didn't like the downbeat ending of real events, she added a final uplifting panel about a pocket (alternative) universe filled with adventures and crime fighting - and people really wanted her to continue that story. The outcome is this book, a hypothetical imagination of what the story would be like if it were to continue as a comic adventure. (Also, the 2D Goggles website)

Like many comics that started on the internet, it doesn't have a continuous story arc, but is a collection of fairly standalone flights of fancy. Where it differs from regular web comics is in its basis, which is always at least inspired by historic quotes and facts, and in its habit of quoting primary sources. Clearly, a lot of research and love has gone into the book. Affection for the characters veritably oozes off the page, while the multiple footnotes per page explain every reference, allusion or detail. Each episode is followed by additional endnotes, which add to the detail from the footnotes, and the book has a further set of appendices on top of that.

The reading experience is quite unusual: almost every line of dialogue and every joke is explained in footnotes. As a German-born man, I principally approve of the explaining of jokes, of course, but it does interrupt the flow of the comic a little. It feels more like getting lost and absorbed in Wikipedia, following one intriguing link after another, with a sense of continuous fascination, than it feels like reading a story.

I guess the book is written for a very specific audience: geeks. Ada Lovelace is, after all, one of the iconic heroes worshipped by 21st century geeks, along Nikola Tesla and other under-appreciated geniuses. This book is not (just) aiming for comedy and entertainment, it wants to get people excited about scientific research and historical figures and events. It wants to educate, and it wants to share the author's fascination and celebrate mankind's capacity for enthusiasm (geekery) itself.

I adored the art / style and loved the enthusiasm. I enjoyed the episodes and the quirky ideas. I appreciated the footnotes and endnotes (unlike other books which have more general knowledge about a topic and sprinkle hidden references that only the cognoscenti can appreciate, Lovelace and Babbage is entirely inclusive of the ignorant, and provides the knowledge to understand each reference), and I think that this book honours Lovelace, Babbage and their contemporaries with clear affection and respect. I loved the whimsiest episodes and ideas the most and couldn't get enough of those.

At times, the book was a little too clever for my taste - I would have loved for Lovelace and Babbage to have a few quirky, whimsical adventures that would have been less bothered with edutainment and more purely narrative-focused. The plot always took last place in the author's priority list, with history, facts, quotes, jokes and whimsy all being more important. Much as I enjoyed the book, I would have liked a little more plot (both inside episodes and between episodes).

Still, if you like steampunk, Victoriana, history, geek culture, comic books, postmodern storytelling and/or a cute aesthetic, then The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage is well worth your time.

Rating: 4/5

Sunday, 3 April 2016

The Lie Tree by Frances Hardinge

I’ve been meaning to read The Lie Tree since it won the Costa Book of the Year Prize - it's unusual for a YA novel to win a big literary award. The premise sounded a little silly, to be honest, in the same way

that a lot of Dystopian YA premises are quite daft.

Faith is the daughter of a Reverend Erasmus Sunderly, a renowned archaeologist / palaeontologist in Victorian Britain. The novel starts when her entire family temporarily relocates to the island of Vane, so her father can join a dig there and provide expert insights.

From the first moment we meet them, they are not the easiest people to be around. Her mother is unceasingly manipulative, trading on her good looks and flirtatious demeanour to get any and every advantage she can obtain. Whether it’s bullying her luggage into the driest spots on the ferry or elbowing her way into the top of any pecking order in any social situation, she’s unbearable and horrible. Her father, meanwhile, is cold, stubborn and judgemental, idolised by Faith not so much for what he does (which is mostly growl, thunder and keep secrets), but who he is – her father and very nearly the voice of God. Only her little brother is okay, because he’s a small child and acts like one.

Even on the ferry, she gathers that there is more to their joint relocation than meets the eye: her family is running away from something nebulous and scandalous. Deeply curious and with a weakness for sneaking and spying on people, Faith makes it her guilty mission to find out what is going on, and to be of use to her father.

The titular Lie Tree does not make its appearance until about halfway through the novel. Up to that point, the story is one of intrigues, secrets and guilt, of scandals and shunnings. It takes a murder and the appearance of aforementioned magical tree for the plot to change gears. It’s still about intrigues and secrets, but finally, it is also suspenseful and pacey.

The second half of the novel is a lot better than the first. It’s still a fairly grim and serious novel about messed up and unpleasant people, with a heroine who chafes against the constraints of society as much as she self-loathes for her failure to be a “good” girl, but at least it entertains despite its bitter flavours.

Rating: 3.5/5

Compared with other novels starring adolescent girls in more constrained times, The Lie Tree is very overtly interested in the oppressive and self-repressive effects of patriarchical societies. There are some standout "teaching moments" in the text.

At one point, Faith looks at herself in the mirror, and concludes that this wild, messy creature she sees is not meant to be a good girl. It is a turning point, and from then on she relishes breaking rules and conventions, getting more and more out of control. As much as the reader might cheer her on initially, some of her actions soon have dire consequences. When a (supposed) baddie calls her a "little viper", I found myself cheering and rooting for the baddies.

At the end of the book, a handful of conversations and thoughts about women and their roles in society occur, some internally (Faith contemplates the way women researchers are treated and remembered by society), others in dialogue (Faith and her mother have a frank conversation). The author might as well have put a giant sign here saying "and the moral of the story is..."

I can't disagree with the author's views, and I don't even mind the somewhat blunt discussion of the book's themes at the end. What does bother me is that, even now, I'm not sure that we haven't been following the "bad guys" all along. Had the novel been written from the perspective of its antagonist(s), it might well have had a more likeable set of heroes. The Sunderly family is full of abhorrent people, and even Faith is, when all her deeds are totalled up, not just failing to be a "good girl", but ultimately, her actions make her not a "good person", either.

Faith is the daughter of a Reverend Erasmus Sunderly, a renowned archaeologist / palaeontologist in Victorian Britain. The novel starts when her entire family temporarily relocates to the island of Vane, so her father can join a dig there and provide expert insights.

From the first moment we meet them, they are not the easiest people to be around. Her mother is unceasingly manipulative, trading on her good looks and flirtatious demeanour to get any and every advantage she can obtain. Whether it’s bullying her luggage into the driest spots on the ferry or elbowing her way into the top of any pecking order in any social situation, she’s unbearable and horrible. Her father, meanwhile, is cold, stubborn and judgemental, idolised by Faith not so much for what he does (which is mostly growl, thunder and keep secrets), but who he is – her father and very nearly the voice of God. Only her little brother is okay, because he’s a small child and acts like one.

Even on the ferry, she gathers that there is more to their joint relocation than meets the eye: her family is running away from something nebulous and scandalous. Deeply curious and with a weakness for sneaking and spying on people, Faith makes it her guilty mission to find out what is going on, and to be of use to her father.

The titular Lie Tree does not make its appearance until about halfway through the novel. Up to that point, the story is one of intrigues, secrets and guilt, of scandals and shunnings. It takes a murder and the appearance of aforementioned magical tree for the plot to change gears. It’s still about intrigues and secrets, but finally, it is also suspenseful and pacey.

The second half of the novel is a lot better than the first. It’s still a fairly grim and serious novel about messed up and unpleasant people, with a heroine who chafes against the constraints of society as much as she self-loathes for her failure to be a “good” girl, but at least it entertains despite its bitter flavours.

Rating: 3.5/5

Addendum:

The Lie Tree is a novel which may be intended to be read in schools. It's clear the author has opinions and wants to communicate them through the novel, so I imagine many a youngster will have to write essays and do critical analysis of the story - at times it feels like it's written for that very purpose.Compared with other novels starring adolescent girls in more constrained times, The Lie Tree is very overtly interested in the oppressive and self-repressive effects of patriarchical societies. There are some standout "teaching moments" in the text.

At one point, Faith looks at herself in the mirror, and concludes that this wild, messy creature she sees is not meant to be a good girl. It is a turning point, and from then on she relishes breaking rules and conventions, getting more and more out of control. As much as the reader might cheer her on initially, some of her actions soon have dire consequences. When a (supposed) baddie calls her a "little viper", I found myself cheering and rooting for the baddies.

At the end of the book, a handful of conversations and thoughts about women and their roles in society occur, some internally (Faith contemplates the way women researchers are treated and remembered by society), others in dialogue (Faith and her mother have a frank conversation). The author might as well have put a giant sign here saying "and the moral of the story is..."

I can't disagree with the author's views, and I don't even mind the somewhat blunt discussion of the book's themes at the end. What does bother me is that, even now, I'm not sure that we haven't been following the "bad guys" all along. Had the novel been written from the perspective of its antagonist(s), it might well have had a more likeable set of heroes. The Sunderly family is full of abhorrent people, and even Faith is, when all her deeds are totalled up, not just failing to be a "good girl", but ultimately, her actions make her not a "good person", either.

Saturday, 19 December 2015

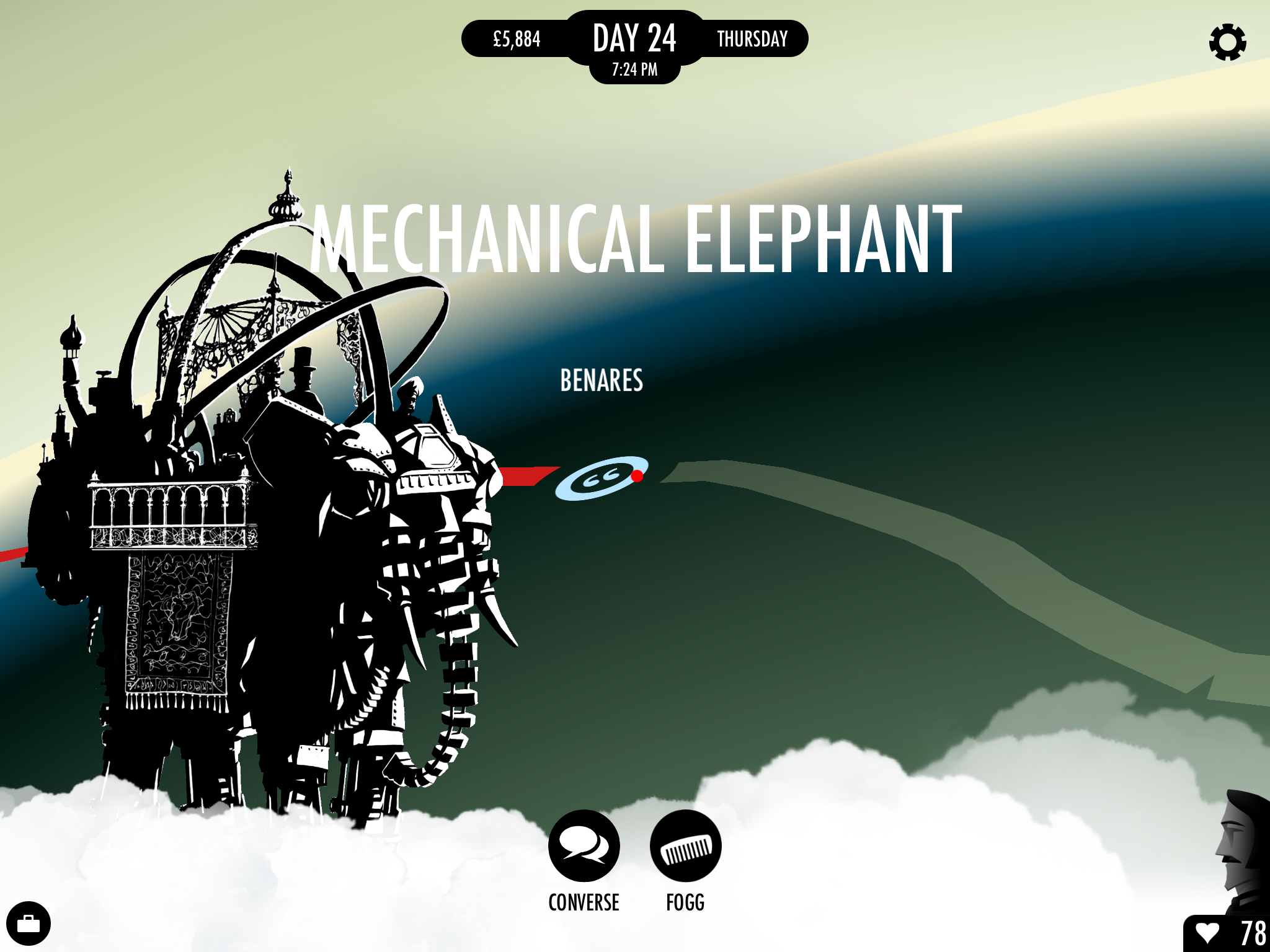

80 Days by inkle

Back in October, I read Strange Charm's review of 80 Days. The review made me buy the game immediately: it sounded like something quite special. And it is.

80 Days is not like most games I have played. It's basically a choose-your-own-adventure story, based primarily on text. The player is Passepartout, valet to Phileas Fogg, travelling around the world for a wager. In every city, you get to choose how and where to travel next, from the connections that are available and which you have been able to discover. (You may not discover every route out of a city)

During every movement from city to city, you choose what to do - look after Fogg (which boosts his health), talk to someone (to find out more about your destination and onwards travelling options), or read the newspaper (to find out about things going on in the world, and sometimes, travel options). In most cities, you can go to a market to buy and sell goods, to a bank to take out loans (which slow you down because you have to wait some day(s) before the funds are cleared), explore to find out onward travel routes and stay overnight. Sometimes, you don't have enough money to continue your journey and you have to find ways to earn it. Other times, Fogg may not have enough health to withstand a particularly arduous route, and you have to let him recuperate. On top of all this, there are a multitude of encounters, on transport and in cities, and adventures and sub plots that you may get embroiled in.

This makes it sound a little dry. It isn't. The characters you meet are a cornucopia of interesting people, of all races, backgrounds, sexes, occupations and opinions. You may meet pirates and royalty, engineers and slave traders, revolutionaries and soldiers. You may get embroiled with a notorious cat burglar or a quest for a robot soul. And the means of transport themselves are fantastically imaginative: this is a steampunk universe realised to its full potential, letting you travel by land, sea, air and, in some places, by even more esoteric means. Not to mention all the little adventures en route: from murder mysteries to grand adventures in the best tradition of Jules Verne and 19th century explorers, this world is chock full of possibilities.

The first time I played the game, I was focused entirely on getting around the world as quickly as possible, so I picked very long, expensive journey legs. I soon ran out of money and ultimately failed to meet the 80 days deadline. The next few times, I played with more focus on balancing income (through trading profitably) with movement. It got fairly easy to get around the world within 80 Days. Then I started geting more and more interested in exploring the world that the creators have produced, and the sub plots. I'm still playing, after dozens of journeys, because I am trying to resolve different mysteries. In all the many, many times I've gone around the world, I have so far only found one way to find a different ending to the game - but that discovery in itself was highly rewarding. I still haven't figured out the Agatha Christie-esque murder mystery on one leg of one itinerary, and I have stumbled across different story paths related to an object you can acquire at a railway station in Western Europe, but I suspect there is a more exciting possible outcome somewhere, if only I could find it.

The plotlines you might stumble into have very different possible outcomes, both in what happens and what it says about the world. You may come into possession of things that some consider the ultimate abomination, while others venerate them, and depending on what you do with them, you may get lots of money or change the world...

At the same time, I'd lie if I didn't admit that some things are a little bit frustrating. As you travel, most circumnavigations will go without really connecting to most of the characters you meet. You may meet two dozen larger-than-life characters and glimpse their lives for the brief duration of the shared journey from A to B, and then never see them again. Sometimes you glimpse something in passing which hints at an intersection with another plotline, had you only chosen differently. Sometimes you read newspaper headlines that tell you about things you have passed. Then again, that is more or less what travelling is like, no?

It is those frustrations which make the game so addictive: I replay again and again because I want to know what I've missed, what I have passed by. When going around the world again and again, I start getting off at different stops, taking different branches, trying to find different routes. This can be hugely rewarding: having passed through an area and witnessed brutality in one journey, I came through the same town on a different route and got a chance to take part in a daring rescue. Another time, in a different place, I had to choose whether to help robbers or fight them, and the two outcomes were vastly different.

I absolutely adore this game. I can't praise it highly enough. Who'd have thought that a text adventure (accompanied by admittedly very nifty, pretty illustrations and a lovely globe) could be so addictive in the age of smartphones?

Rating: 5/5

Go buy it now!

80 Days is not like most games I have played. It's basically a choose-your-own-adventure story, based primarily on text. The player is Passepartout, valet to Phileas Fogg, travelling around the world for a wager. In every city, you get to choose how and where to travel next, from the connections that are available and which you have been able to discover. (You may not discover every route out of a city)

During every movement from city to city, you choose what to do - look after Fogg (which boosts his health), talk to someone (to find out more about your destination and onwards travelling options), or read the newspaper (to find out about things going on in the world, and sometimes, travel options). In most cities, you can go to a market to buy and sell goods, to a bank to take out loans (which slow you down because you have to wait some day(s) before the funds are cleared), explore to find out onward travel routes and stay overnight. Sometimes, you don't have enough money to continue your journey and you have to find ways to earn it. Other times, Fogg may not have enough health to withstand a particularly arduous route, and you have to let him recuperate. On top of all this, there are a multitude of encounters, on transport and in cities, and adventures and sub plots that you may get embroiled in.

This makes it sound a little dry. It isn't. The characters you meet are a cornucopia of interesting people, of all races, backgrounds, sexes, occupations and opinions. You may meet pirates and royalty, engineers and slave traders, revolutionaries and soldiers. You may get embroiled with a notorious cat burglar or a quest for a robot soul. And the means of transport themselves are fantastically imaginative: this is a steampunk universe realised to its full potential, letting you travel by land, sea, air and, in some places, by even more esoteric means. Not to mention all the little adventures en route: from murder mysteries to grand adventures in the best tradition of Jules Verne and 19th century explorers, this world is chock full of possibilities.

The first time I played the game, I was focused entirely on getting around the world as quickly as possible, so I picked very long, expensive journey legs. I soon ran out of money and ultimately failed to meet the 80 days deadline. The next few times, I played with more focus on balancing income (through trading profitably) with movement. It got fairly easy to get around the world within 80 Days. Then I started geting more and more interested in exploring the world that the creators have produced, and the sub plots. I'm still playing, after dozens of journeys, because I am trying to resolve different mysteries. In all the many, many times I've gone around the world, I have so far only found one way to find a different ending to the game - but that discovery in itself was highly rewarding. I still haven't figured out the Agatha Christie-esque murder mystery on one leg of one itinerary, and I have stumbled across different story paths related to an object you can acquire at a railway station in Western Europe, but I suspect there is a more exciting possible outcome somewhere, if only I could find it.

The plotlines you might stumble into have very different possible outcomes, both in what happens and what it says about the world. You may come into possession of things that some consider the ultimate abomination, while others venerate them, and depending on what you do with them, you may get lots of money or change the world...

At the same time, I'd lie if I didn't admit that some things are a little bit frustrating. As you travel, most circumnavigations will go without really connecting to most of the characters you meet. You may meet two dozen larger-than-life characters and glimpse their lives for the brief duration of the shared journey from A to B, and then never see them again. Sometimes you glimpse something in passing which hints at an intersection with another plotline, had you only chosen differently. Sometimes you read newspaper headlines that tell you about things you have passed. Then again, that is more or less what travelling is like, no?

It is those frustrations which make the game so addictive: I replay again and again because I want to know what I've missed, what I have passed by. When going around the world again and again, I start getting off at different stops, taking different branches, trying to find different routes. This can be hugely rewarding: having passed through an area and witnessed brutality in one journey, I came through the same town on a different route and got a chance to take part in a daring rescue. Another time, in a different place, I had to choose whether to help robbers or fight them, and the two outcomes were vastly different.

I absolutely adore this game. I can't praise it highly enough. Who'd have thought that a text adventure (accompanied by admittedly very nifty, pretty illustrations and a lovely globe) could be so addictive in the age of smartphones?

Rating: 5/5

Go buy it now!

Monday, 29 June 2015

To Say Nothing of the Dog by Connie Willis

To Say Nothing of the Dog is the second book in a series. It's sort of a sequel, but each book is a standalone novel. There are also huge differences in the general mood of the books. Some characters from Doomsday Book reappear. Most don't.

The start of To Say Nothing of the Dog is actually quite similar to that of Doomsday Book. We're back in the world of academics and time travellers, and the book starts once again with a heavily disoriented person semi-hallucinating their way through a tricky environment. This time, the disorientation is the result of time lag (like jet lag, I guess), rather than fever / infection.

Characters once again have a habit of talking past each other. Few people listen, everyone talks through their own concerns, completely self-absorbed, barely paying attention to the other half of each dialogue.This, too, is a hallmark readers of Doomsday Book will be well familiar with.

However, things quickly stabilise and take a completely different direction. This is not a book about disease, peril, and tragedy. Instead, it is a light comedy, heavily inspired by Three Men in a Boat, Jeeves and Wooster, Agatha Christie Mysteries and Shakespearean comedies of errors. Soon, people actually listen to each other and work together in ways that hardly anyone in Doomsday Book ever does.

The plot is as convoluted as a comedy of errors tends to be. A time traveller has thoughtlessly smuggled a cat through time, after rescuing her from being drowned. As this introduced an 'incongruity', the historians desperately want to solve any paradoxes, and send a second (seriously disoriented) time traveller back to help mop up the problems. All this while everyone is terribly busy on behalf of a generous sponsor who is rebuilding a cathedral that was destroyed in WW2 - and who insists on every little detail being found and recreated faithfully, especially the missing 'Bishop's Bird Stump' - some kind of hideous vase. Entanglements are complicated as the time travellers prevent people from meeting each other, cause others to meet each other, and try to impede or cause romantic alliances in order to shift the course of history back where it belongs, and get the right people married to each other...

If I'm perfectly honest, To Say Nothing of the Dog was a little boring. I could see the wry wit and the genteel bemusement that infused the entire book, but it was not the sort of humour that makes me guffaw. The plot, meanwhile, never built up a sense of genuine peril. Doomsday Book was a novel of gut-wrenching tragedies and terrible horrors. To Say Nothing of the Dog is a novel of light entertainment. It doesn't have the biting wit of Oscar Wilde, but a more mellow sense of lighthearted affectionate cheer. It also felt like a novel which might require people to be familiar with a lot of works to fully appreciate it. I could see, obliquely, what was being referenced, but felt quite ignorant as I suspect a lot of details passed me by entirely.

So, if you are familiar with, and a big fan of, Three Men in a Boat, Jeeves and Wooster, and that entire genre of work, then you might adore this book. It pays homage and doffs its cap and generally adores those works, too. It's fuller of references than a Pixar movie, while being tonally quite similar to those works (I assume).

If you're looking for slightly darker humour (personally, I prefer the Ladykillers / Arsenic and Old Lace / Kind Hearts and Coronets type of chuckles), then you may be a bit disappointed. And if you expect anything like Doomsday Book, you'll be in for a surprise.

Rating: 3/5

The start of To Say Nothing of the Dog is actually quite similar to that of Doomsday Book. We're back in the world of academics and time travellers, and the book starts once again with a heavily disoriented person semi-hallucinating their way through a tricky environment. This time, the disorientation is the result of time lag (like jet lag, I guess), rather than fever / infection.

Characters once again have a habit of talking past each other. Few people listen, everyone talks through their own concerns, completely self-absorbed, barely paying attention to the other half of each dialogue.This, too, is a hallmark readers of Doomsday Book will be well familiar with.

However, things quickly stabilise and take a completely different direction. This is not a book about disease, peril, and tragedy. Instead, it is a light comedy, heavily inspired by Three Men in a Boat, Jeeves and Wooster, Agatha Christie Mysteries and Shakespearean comedies of errors. Soon, people actually listen to each other and work together in ways that hardly anyone in Doomsday Book ever does.

The plot is as convoluted as a comedy of errors tends to be. A time traveller has thoughtlessly smuggled a cat through time, after rescuing her from being drowned. As this introduced an 'incongruity', the historians desperately want to solve any paradoxes, and send a second (seriously disoriented) time traveller back to help mop up the problems. All this while everyone is terribly busy on behalf of a generous sponsor who is rebuilding a cathedral that was destroyed in WW2 - and who insists on every little detail being found and recreated faithfully, especially the missing 'Bishop's Bird Stump' - some kind of hideous vase. Entanglements are complicated as the time travellers prevent people from meeting each other, cause others to meet each other, and try to impede or cause romantic alliances in order to shift the course of history back where it belongs, and get the right people married to each other...

If I'm perfectly honest, To Say Nothing of the Dog was a little boring. I could see the wry wit and the genteel bemusement that infused the entire book, but it was not the sort of humour that makes me guffaw. The plot, meanwhile, never built up a sense of genuine peril. Doomsday Book was a novel of gut-wrenching tragedies and terrible horrors. To Say Nothing of the Dog is a novel of light entertainment. It doesn't have the biting wit of Oscar Wilde, but a more mellow sense of lighthearted affectionate cheer. It also felt like a novel which might require people to be familiar with a lot of works to fully appreciate it. I could see, obliquely, what was being referenced, but felt quite ignorant as I suspect a lot of details passed me by entirely.

So, if you are familiar with, and a big fan of, Three Men in a Boat, Jeeves and Wooster, and that entire genre of work, then you might adore this book. It pays homage and doffs its cap and generally adores those works, too. It's fuller of references than a Pixar movie, while being tonally quite similar to those works (I assume).

If you're looking for slightly darker humour (personally, I prefer the Ladykillers / Arsenic and Old Lace / Kind Hearts and Coronets type of chuckles), then you may be a bit disappointed. And if you expect anything like Doomsday Book, you'll be in for a surprise.

Rating: 3/5

Friday, 13 March 2015

The Twyning by Terence Blacker

The Twyning is set in a small British town in Victorian times. There, a kindgom of rats lives in the sewers, while, in the town above, an obsessed scientist is intent on launching a war against rats.

The novel alternates between telling the story of Efren, a young rat, and Dogboy, an urchin who earns pennies working for the scientist and the town's rat catcher.

It's rare to read a book starring rats, which makes this an instantly original and off-beat story. It strikes an interesting balance between animalistic and anthropomorphic qualities when telling the rat's view of events. Physically, on the outside, they are definitely rats, their movements and actions described in prose that skilfully draws them very much as rodents. Internally, however, they are not quite so different from humans. True, they can get much more absorbed by tunnel vision and be of a very singular purpose in a crisis, but when not in crisis, they are part of a kingdom with different courts, different vocations, intrigues and power plays... This combination gives them a slightly surreal aspect - it reminded me a little of the way the Fantastic Mr Fox movie combined savagery with civilisation...

I would have preferred it if the rats were more animalistic in their minds - they don't come close to the benchmark set by the amazing In Great Waters for having convincing non-human intelligent characters. I also felt some of the monologuing was a bit unnecessary and un-ratlike. But neither of those things are at the heart of the story. At its heart, this is the tale of a brave young rat trying to find, and later decide, his place in the world. It's also a love story, between Efren and Malaika, a female rat who is not merely a love interest, but very much her own rat with her own perspective and motivation.

The human tale, meanwhile, is one of urchins and underclass people struggling to create a place for themselves in a world that sees no value in them. Oh, and that is a love story too, though not romantic love.

The byline on the book, "A story of love, war and rats" is a perfect summary. The love between different characters is palpable and utterly believable, utterly heart-warming and sometimes heart-breaking. The story of war is, essentially, satirical in the human narrative, but a struggle for survival and against genocide for the rats.

I thoroughly enjoyed this book. It's original, quirky, and heartfelt. It's fast-paced and a page-turner. I would highly recommend it to everyone (except those with a strong phobia of rats).

Rating: 4.5/5

The novel alternates between telling the story of Efren, a young rat, and Dogboy, an urchin who earns pennies working for the scientist and the town's rat catcher.

It's rare to read a book starring rats, which makes this an instantly original and off-beat story. It strikes an interesting balance between animalistic and anthropomorphic qualities when telling the rat's view of events. Physically, on the outside, they are definitely rats, their movements and actions described in prose that skilfully draws them very much as rodents. Internally, however, they are not quite so different from humans. True, they can get much more absorbed by tunnel vision and be of a very singular purpose in a crisis, but when not in crisis, they are part of a kingdom with different courts, different vocations, intrigues and power plays... This combination gives them a slightly surreal aspect - it reminded me a little of the way the Fantastic Mr Fox movie combined savagery with civilisation...

I would have preferred it if the rats were more animalistic in their minds - they don't come close to the benchmark set by the amazing In Great Waters for having convincing non-human intelligent characters. I also felt some of the monologuing was a bit unnecessary and un-ratlike. But neither of those things are at the heart of the story. At its heart, this is the tale of a brave young rat trying to find, and later decide, his place in the world. It's also a love story, between Efren and Malaika, a female rat who is not merely a love interest, but very much her own rat with her own perspective and motivation.

The human tale, meanwhile, is one of urchins and underclass people struggling to create a place for themselves in a world that sees no value in them. Oh, and that is a love story too, though not romantic love.

The byline on the book, "A story of love, war and rats" is a perfect summary. The love between different characters is palpable and utterly believable, utterly heart-warming and sometimes heart-breaking. The story of war is, essentially, satirical in the human narrative, but a struggle for survival and against genocide for the rats.

I thoroughly enjoyed this book. It's original, quirky, and heartfelt. It's fast-paced and a page-turner. I would highly recommend it to everyone (except those with a strong phobia of rats).

Rating: 4.5/5

Saturday, 14 February 2015

A Darker Shade of Magic by Victoria Schwab

A Darker Shade of Magic is a book that knows what it wants to achieve: swashbuckling adventure, likably spunky but tough heroes, plenty of energy and fun. With magic. It doesn't do too badly.

There are four parallel Earths in this book, each just a quick dimension apart. Each has a city called London in the same place on the Thames, but they have different languages, different countries, different histories. The biggest difference, however, is the level and role of magic in each city.

There are only two magicians left who can travel between worlds: Kell, from Red London, and Holland, from White London. They act as messengers between the royal families of the three Londons that are still accessible. Black London has been sealed off to prevent its apocalypse from spreading into the other dimensions.

Kell is our hero, and the story really kicks off when he smuggles an artefact (which is treason) that turns out to be a relic from Black London (which makes it powerful and dangerous). Suddenly, all kinds of nefarious characters and thugs are after Kell. To make things worse, he gets entangled with Lila, a tough teenaged orphan girl from Grey London who wants nothing more than to be a pirate captain and see the world...

A Darker Shade of Magic has all the right ingredients: a good pace, repartee between the good guys, sinister and creepy baddies, adventure and magic... it's great fun to read.

It's not flawless: there are some holes in the plot, and while it is nominally set in (four) London(s), Grey London doesn't quite feel like UK London to me. In terms of plotholes, it's never quite clear what the royal families in the different Londons have to say to each other / why any connection continues to exist, and what magic can and can't do is quite nebulous. It feels a little as if the author hasn't quite worked out the workings of magic in her worlds. Still, these are flaws only some (overly pernickety) readers will mind: I think most readers who like to read the occasional fantasy novel will thoroughly enjoy A Darker Shade of Magic. I certainly did.

Rating: 4/5

There are four parallel Earths in this book, each just a quick dimension apart. Each has a city called London in the same place on the Thames, but they have different languages, different countries, different histories. The biggest difference, however, is the level and role of magic in each city.

- Grey London has almost no magic - and matches our London under Mad King George.

- Red London is rich in magic, and people live in harmony with the magic.

- White London is poor in magic, and people strive to steal, control, and dominate the magic as much as they can.

- Black London is dead: here, people had let themselves be controlled by their magic, and the world had experienced a mysterious apocalypse as a result.

There are only two magicians left who can travel between worlds: Kell, from Red London, and Holland, from White London. They act as messengers between the royal families of the three Londons that are still accessible. Black London has been sealed off to prevent its apocalypse from spreading into the other dimensions.

Kell is our hero, and the story really kicks off when he smuggles an artefact (which is treason) that turns out to be a relic from Black London (which makes it powerful and dangerous). Suddenly, all kinds of nefarious characters and thugs are after Kell. To make things worse, he gets entangled with Lila, a tough teenaged orphan girl from Grey London who wants nothing more than to be a pirate captain and see the world...

A Darker Shade of Magic has all the right ingredients: a good pace, repartee between the good guys, sinister and creepy baddies, adventure and magic... it's great fun to read.

It's not flawless: there are some holes in the plot, and while it is nominally set in (four) London(s), Grey London doesn't quite feel like UK London to me. In terms of plotholes, it's never quite clear what the royal families in the different Londons have to say to each other / why any connection continues to exist, and what magic can and can't do is quite nebulous. It feels a little as if the author hasn't quite worked out the workings of magic in her worlds. Still, these are flaws only some (overly pernickety) readers will mind: I think most readers who like to read the occasional fantasy novel will thoroughly enjoy A Darker Shade of Magic. I certainly did.

Rating: 4/5

Thursday, 29 January 2015

Cannonbridge by Jonathan Barnes

|

| Cumberba... erm, I mean, Cannonbridge. |

Toby Judd, our present day hero, is an unknown academic, a professor of literature who has not made a big name for himself. The novel starts with a rather devastating experience: his girlfriend leaves him for a more successful pop-academic, whose new work about Cannonbridge is annoyingly bestselling and shallow and populist. Devastated by his humiliation, Toby suddenly has an epiphany: Cannonbridge never existed! He's a literary hoax! And Toby promptly uses his inaugural professorial lecture to present that hypothesis, before being interrupted a few minutes into his raving rants and kicked out of his university for being a lunatic.

Only he isn't mad, and suddenly those who believe in a conspiracy start dying...

Meanwhile, in the Victorian age, Matthew Cannonbridge meets one famous writer after another, and grows increasingly sinister in aspect.

I really enjoyed Jonathan Barnes' first novel, The Somnambulist, but did not enjoy its sequel, The Domino Men. When I saw that a new standalone novel is coming out, I was curious. The premise sounded promising and intriguing. Unfortunately, Cannonbridge was a bad disappointment.

Our hero, Toby Judd, is a bit of a wet blanket. That's fine, but there is no logic behind his sudden conviction that Cannonbridge is a hoax. He just suddenly has a feeling that Cannonbridge has no reality, and then he irrationally decides to base a lecture on that feeling without being able to properly rationalise his own theory. That seems a bit unconvincing.

Logic is, in fact, in very short supply in the novel. As in: there is no internal logic whatsoever. There is a big conspiracy killing people, not because it makes sense for them to kill people, but because people dying is necessary to give the plot some momentum and drag Toby out of his academic exile.

Meanwhile, Matthew Cannonbridge pops up all over the Victorian place without actually having a clear effect. The central plot is that Matthew Cannonbridge is the writer of his age. Yes, he has encountered all the others, but it's his works (rather than theirs) which is most well-remembered. He is, in effect, the Shakespeare of that age (writing prose rather than drama), only of course he never actually writes anything - he has written, without having to go through the writing. The problem is that it's never clear whether the works of his contemporaries still exist (in the form they do in our world) or not. If they do exist, then there is no compelling reason why Cannonbridge's writings have eclipsed all the others. If the other works do not exist - if, in fact, he somehow detracts from all the writers of his age by meeting them, passively leeching creativity and influence and fame off them - then it hardly matters that he met them all, and it would not matter much to his fame. Unfortunately, I have no idea which is the case - he seems to meet the Shelleys the night that Frankenstein was first conceived, and it seems as if that meeting results in the book never being written, or not in its famous form - but he meets most of the other writers mid-career or even towards the end of their careers.

I found Cannonbridge a struggle to read, not because of any difficulties with the language or ideas, but because it soon became very frustrating and repetitive and boring. For a long while, the basic pattern is:

- Toby meets someone. That someone dies.

- Cannonbridge meets someone famous, and is so inherently charismatic that he makes an impression on them, then he disappears.

- Reiterate.

Later on, the novel aims for a sense of the uncanny. A strangely calm but super-effective hitman, a sinister island, some monstrous events... the sort of things that I suspect are Lovecraftian (I still haven't read more than one Lovecraft short story, so I still use that term second-hand or third-hand). Perhaps even a bit like Lost - a build up of uncanny that has no internal logic whatsoever.

Unfortunately, the novel never really succeeds at building up tension, or horror, or anything but exasperation. The final resolution is... well, silly would be the word I'd choose, and the final twist is an excuse for shoddy writing in earlier chapters. Truthfully, I only finished it because I got a free copy through Netgalley and felt obligated to read it all the way to the end so I could write a review.

I'd give this one a miss.

Rating: 1/5

Sunday, 11 January 2015

Conjugal Rites by Paul Magrs

As a reader, my awareness of the publishing industry and its trends is patchy: I notice some big trends sometimes (kinky porn, ever since 50 Shades, and general popularity of Young Adult and 'Forever Young Adult' literature - books that have YA-style plots and pacing, but grown-up characters), but other trends pass me by.

So, is there a trend for "senior citizen young adult" literature out there? If not, then I suspect Paul Magrs may sneakily have been carving out a genre for himself while everyone else wasn't paying attention.

I enjoyed the first two Brenda and Effie mysteries without ever thinking about its genre. Cheerful, light-hearted gothic fun, with fairly pacey plots, a mischievous disposition, and older protagonists. But that alone would not make a new genre: the 100-year-old-man-who-climbed-out-of-a-window-and-disappeared, for example, is hardly a book aimed at an older audience.

It's not until I read Conjugal Rites that I started to suspect that something a bit unusual was going on.

It's not until I read Conjugal Rites that I started to suspect that something a bit unusual was going on.

Brenda and Effie are both older ladies. Brenda, we find out in the first novel, was created by Doktor Frankenstein, intended to be the bride for his first creature. However, she has fled from that fate, and, after hundreds of years of trying to find a way to fit in, she has set up a B&B in Whitby. Effie, her neighbour, is a spinster and a descendant from a long line of witches. She's a bit fierce, a bit gullible, but very close to Brenda. Together, they have gothic adventures, whether being seduced by Dracula or trying to uncover the sinister secrets of a con man who makes women younger. The two big old hotels in town each have their back histories and charismatic owners (the sinister and evil Mrs Claus, running a Christmas-themed hotel with cannibalism and enslaved elves, while the other hotel is run by the widow of an elderly London-based Chinese Criminal Mastermind and Supervillain). It's all gloriously playful with gothic tropes, and good fun.

In Conjugal Rites, some of Brenda and Effie's former adversaries are again up to no good. One is running a night time talk radio show that somehow compels everyone to spill personal secrets and tell the juiciest, most indiscrete gossip about each other, while another has arranged for a suspicious congress for retired superheroes. Worst of all, it looks like Brenda's oldest adversary has been summoned to town...

While reading the book, some things jarred a bit: frequent repetition, and a habit of summing up everything that has happened so far every other chapter or so. It's almost like one of those TV shows, where, right after the ad break, characters quickly discuss something that happened previously, so that the audience remembers the context for the next scene. At first, I thought this was slightly clumsy writing and I recalled that similar things had bothered me a little in previous volumes. Then a penny dropped: what if it was not clumsy? What if, in fact, this was a planned out strategy? The regularity of these little plot-summary-moments was just too carefully timed. Suddenly, the somewhat strange look and feel of the covers of these books started to make sense. The larger format, too. I read this one on Kindle, but I'd now bet that these books were all printed in slightly-larger-than-standard print, with a bit more spacing between the rows. I'd been reading books written, designed, printed, and created for an elderly audience with weaker eyes and a need for memories to be frequently refreshed. I'd read several volumes without ever suspecting that I was not the target audience.

Maybe there are many books like this series out there. Maybe this isn't new to anyone else. Perhaps I was the only one thinking that older people were mostly targeted by Mills & Boon and Danielle Steel and all those lavender-y, awful-looking romance books, rather than anything fun and adventurous. In that case, shame on me. I used to enjoy watching Murder She Wrote and Columbo and other crime movies meant for older viewers; I should hardly be surprised that there are gothic adventures written explicitly for them, too. (I think someone should make te Brenda and Effie books into a TV series: clearly, with the ageing population, they should have a ready-made market ready)

Once I got past that realisation, the book continued to be pleasingly diverting. There are some aspects where I wanted things to go down a different route: hell features in this novel, but it is not a hell that convinced me. Worse, the entire plot arc about Brenda's erstwhile suitor was uncomfortable and troubling to read. (For a Brenda and Effie novel, there really isn't enough Brenda in this one...)

So, not quite up there with the first volume in terms of its fun, but still a pleasing novel - and the only young-adult-for-senior-citizens series of gothic adventure novels that I'm aware of. Hats off to Paul Magrs for eemingly creating an entire market niche, which he totally owns!

Rating: 3/5

So, is there a trend for "senior citizen young adult" literature out there? If not, then I suspect Paul Magrs may sneakily have been carving out a genre for himself while everyone else wasn't paying attention.

I enjoyed the first two Brenda and Effie mysteries without ever thinking about its genre. Cheerful, light-hearted gothic fun, with fairly pacey plots, a mischievous disposition, and older protagonists. But that alone would not make a new genre: the 100-year-old-man-who-climbed-out-of-a-window-and-disappeared, for example, is hardly a book aimed at an older audience.

It's not until I read Conjugal Rites that I started to suspect that something a bit unusual was going on.

It's not until I read Conjugal Rites that I started to suspect that something a bit unusual was going on.Brenda and Effie are both older ladies. Brenda, we find out in the first novel, was created by Doktor Frankenstein, intended to be the bride for his first creature. However, she has fled from that fate, and, after hundreds of years of trying to find a way to fit in, she has set up a B&B in Whitby. Effie, her neighbour, is a spinster and a descendant from a long line of witches. She's a bit fierce, a bit gullible, but very close to Brenda. Together, they have gothic adventures, whether being seduced by Dracula or trying to uncover the sinister secrets of a con man who makes women younger. The two big old hotels in town each have their back histories and charismatic owners (the sinister and evil Mrs Claus, running a Christmas-themed hotel with cannibalism and enslaved elves, while the other hotel is run by the widow of an elderly London-based Chinese Criminal Mastermind and Supervillain). It's all gloriously playful with gothic tropes, and good fun.

In Conjugal Rites, some of Brenda and Effie's former adversaries are again up to no good. One is running a night time talk radio show that somehow compels everyone to spill personal secrets and tell the juiciest, most indiscrete gossip about each other, while another has arranged for a suspicious congress for retired superheroes. Worst of all, it looks like Brenda's oldest adversary has been summoned to town...

While reading the book, some things jarred a bit: frequent repetition, and a habit of summing up everything that has happened so far every other chapter or so. It's almost like one of those TV shows, where, right after the ad break, characters quickly discuss something that happened previously, so that the audience remembers the context for the next scene. At first, I thought this was slightly clumsy writing and I recalled that similar things had bothered me a little in previous volumes. Then a penny dropped: what if it was not clumsy? What if, in fact, this was a planned out strategy? The regularity of these little plot-summary-moments was just too carefully timed. Suddenly, the somewhat strange look and feel of the covers of these books started to make sense. The larger format, too. I read this one on Kindle, but I'd now bet that these books were all printed in slightly-larger-than-standard print, with a bit more spacing between the rows. I'd been reading books written, designed, printed, and created for an elderly audience with weaker eyes and a need for memories to be frequently refreshed. I'd read several volumes without ever suspecting that I was not the target audience.

Maybe there are many books like this series out there. Maybe this isn't new to anyone else. Perhaps I was the only one thinking that older people were mostly targeted by Mills & Boon and Danielle Steel and all those lavender-y, awful-looking romance books, rather than anything fun and adventurous. In that case, shame on me. I used to enjoy watching Murder She Wrote and Columbo and other crime movies meant for older viewers; I should hardly be surprised that there are gothic adventures written explicitly for them, too. (I think someone should make te Brenda and Effie books into a TV series: clearly, with the ageing population, they should have a ready-made market ready)

Once I got past that realisation, the book continued to be pleasingly diverting. There are some aspects where I wanted things to go down a different route: hell features in this novel, but it is not a hell that convinced me. Worse, the entire plot arc about Brenda's erstwhile suitor was uncomfortable and troubling to read. (For a Brenda and Effie novel, there really isn't enough Brenda in this one...)

So, not quite up there with the first volume in terms of its fun, but still a pleasing novel - and the only young-adult-for-senior-citizens series of gothic adventure novels that I'm aware of. Hats off to Paul Magrs for eemingly creating an entire market niche, which he totally owns!

Rating: 3/5

Wednesday, 17 December 2014

The Invisible Library by Genevieve Cogman

The Invisible Library starts out with aplomb. Irene, our protagonist, is an Undercover Librarian. That’s it, I’m

already sold on this book. She’s on a secret mission to retrieve a rare and

unique book from the library of a wizards’ boarding school. Seriously, if you

aren’t immediately putting this book in your shopping basket after that

sentence, there is something wrong with you. Her heist - yes, a full-blown

heist with booby-traps and tight timings and a great big chase and a narrow

escape - is fast, thrilling, witty, and only the first chapter.

After

returning to the Invisible Library (a mysterious, huge, timeless entity, existing

between dimensions and parallel worlds; a library where people can travel for

days among the bookshelves to get from one area to another, set inside an even

more mysterious city that the Librarians never enter, occasionally glimpse from

their windows, and know nothing about), Irene suddenly finds herself given a

new, urgent assignment in different universe, and her first ever apprentice. Oh, and she actually has a personal nemesis among her Librarian colleagues.

The

Invisible Library is great fun to read. A brisk pace, a sense of humour, and a likeable

protagonist make this a near-perfect novel for grown-ups whose inner kids (and

inner young adults) are alive and well and thirsting for tales of adventure.

I’ve seen it

compared to Doctor Who, I’m sure it’ll be compared to Harry Potter, and it’ll

probably get compared to every Anglophile novel full of vim and fun that’s ever

been written. These comparisons will all be well-earned: it’s a highly

pleasurable read. Big adventures, clever detectives, magic, fey folk, cyborgs,

dragons, zeppelins, secrets, conspiracies... and best of all, it has unlimited potential

for future novels.

Let’s put it

like this: if you like Paul Magrs’ Brenda and Effie series, or Indiana Jones,

or Ben Aaronovitch’s Peter Grant novels, or Inkheart, then I think it’s a

fairly safe bet that The Invisible Library will be right up your street, too.

Rating:

4.5/5

Sunday, 2 March 2014

The Quick by Lauren Owen

The Quick is a novel set in Victorian England, mostly in London. The book starts with an atmospheric chapter about two children growing up in an almost-abandoned mansion near York, looked after by a servant while a distant father is mostly an ominous concept, rather than any reality. A wonderfully dramatic series of events with just the right level of mystery and scariness occurs. The chapter is full of rich descriptions, atmosphere and the children are perfectly set up to be the heroes of a tale...

...only then the narrative skips, and they are adults, and we're not following the girl, but the withdrawn, aloof boy, and there's so much less drama and atmosphere as he goes to University, finds himself, meanders around the edges of high society without any purpose or drive...

...for ages and ages and AGES...

...until there are a few plot turns, first all about society and relationships, and then, only then, after a very long time, does the narrative drift into a slightly more Gothic Victorian tale.

And then, for some more ages and ages and ages, it switches perspective, as we read the scientific diary of a man who will become Doctor Knife...

As you can guess from my review thus far, the book struggles badly with pacing (or the lack of it). Perspectives shift quite frequently, and the characters it shifts to are not always interesting. Still, for each, we get a whole back story (decades of it), and this is a book which really believes in concluding things, because even after the climactic confrontations, we still get ending after anding after ending, until we know for almost every single character what they did with the rest of their lives.

A looooong intro and a looooong outro: not the hallmarks of modern novel pacings. Perhaps that makes it authentic - I did not love Mary Shelley's Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus. Perhaps the author was trying to emulate that novel and its contemporaries, and perhaps she succeeded.

For me, the novel quickly drifted from "descriptions which add to the atmosphere" into "details that I really did not care about". People make tea, eat, think about domestic matters, run into other people and scenes that have no dramatic energy at all. Sometimes, there are things revealed about characters (a woman, sleeping in another woman's bed, notices the smell of sweaty hair, the general untidiness and unVictorian lack of primness), but at other times, the books is just filled to the rafters with filler descriptions and filler scenes and meaningless padding.

There is a time in this novel when it actually has pace and energy - when Shadwell and Adeline appear. Of course, this is first sabotaged, by being given their entire back story in great detail, but once they're actually doing stuff, the novel actually gains a bit of momentum, for a while.

The novel struggles with some serious mistakes: It gives us too much detail about the wrong characters - or perhaps the characters it gives a lot of detail about instantly become boring because they lose their mystique. Charlotte is interesting, but spends a good chunk of the novel hidden away and disempowered inside her mansion, while her brother, basically a bit of a wet blanket, goes to uni, not doing anything interesting at all for ages. Dr Mould is not the most interesting of characters - there is very little complexity in him. Liza is okay as a character (again, not exactly an original one, but at least vaguely interesting to encounter), and Adeline and Shadwell have at least some semblance of an interesting dynamic, but the characters which intrigued me were all the ones with a little mystery left to them. Rafferty, Makeweight, Mrs Price...

In the end, I think people who like Fin de Siecle, original Gothic novels (Frankenstein, Dracula, Jekyll & Hyde, etc.) might enjoy this evocation of that literary genre. But people like me - who enjoy the aesthetic but want a bit more pace and adventure, and less description and fewer backstories - are not going to enjoy The Quick.

Rating: 2/5

...only then the narrative skips, and they are adults, and we're not following the girl, but the withdrawn, aloof boy, and there's so much less drama and atmosphere as he goes to University, finds himself, meanders around the edges of high society without any purpose or drive...

...for ages and ages and AGES...

...until there are a few plot turns, first all about society and relationships, and then, only then, after a very long time, does the narrative drift into a slightly more Gothic Victorian tale.

And then, for some more ages and ages and ages, it switches perspective, as we read the scientific diary of a man who will become Doctor Knife...

As you can guess from my review thus far, the book struggles badly with pacing (or the lack of it). Perspectives shift quite frequently, and the characters it shifts to are not always interesting. Still, for each, we get a whole back story (decades of it), and this is a book which really believes in concluding things, because even after the climactic confrontations, we still get ending after anding after ending, until we know for almost every single character what they did with the rest of their lives.

A looooong intro and a looooong outro: not the hallmarks of modern novel pacings. Perhaps that makes it authentic - I did not love Mary Shelley's Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus. Perhaps the author was trying to emulate that novel and its contemporaries, and perhaps she succeeded.