Vanished is part mystery thriller, part coming of age tale and part chronicle of recent history. Ahmed Masoud, a Palestinian ex-pat living in the UK, set out to introduce readers to a part of the world that most of us will never set foot in: Gaza.

The novel is framed by events of 2014: our protagonist, Omar, leaves his wife and son in London to make his way to Gaza during the bombardment of the strip by Israeli forces. Having had news that his former home has been bombed, and unable to reach his remaining relatives and friends by phone, he feels a strong obligation to return, no matter what the cost. En route, he begins to write down his life story, so that his toddling son might one day understand what drove Omar to leave him behind, should he not return.

Omar starts his life story with the year he decided to become a detective and find out what had happened to his own father. Omar was a baby when his father disappeared one night, and by the time he is eight years old, he wants nothing more than to find out how and why. His investigations are dangerous, however. Over the course of his quest, he finds himself embroiled with the Israeli security forces, rebel fighters, nationalist and Islamist politics, the peace process and the intifadas.

Vanished is a very readable novel. The prose is plain and matter of fact. The narrative moves briskly even when events don't (sometimes, years pass between significant events and paragraphs of text). Our protagonist's struggles are all too authentic. However, in its desire to present 25 years' worth of history alongside the mystery plot, the novel inevitably loses focus as time goes on - just as Omar's quest becomes sidelined in his life as larger events take hold of him.

There are many things about life in Gaza that seem a little surprising to outsiders like me. Though it's densely populated, there is a very strong sense of community in each street. People know each other. Similarly, everyone knows who runs the Israeli army in Gaza, and everyone refers to him by his first name. I cannot be the only one who is constantly perplexed that Benjamin Netanyahu is referred to as "Bibi" by politicians and media alike. After reading Vanished, I must conclude that this way of talking about people, which sounds overly familiar to my ears, must be the norm in that part of the world. Perhaps most importantly, the Gaza in this novel is a living, breathing enclave, with people leading everyday lives and having everyday concerns. Children go to school, treats, sweets and beatings are dished out by the grown ups, young people head to university and make plans for their futures and careers, while dreaming about and trying to hang out with members of the opposite sex...

However, the book does have its fair share of flaws and problems. Perhaps the most unsurprising is the way Israelis are portrayed: monstrous child-raping killers, nameless oppressors, bullies. There is no Israeli character with any redeeming features in the book: they are clearly the villains of the piece. For a book which handles shades of grey and complexities between the different resistance groups and political factions among Palestinians quite well, this treatment of Israel is a little too simplistic. Then again, I doubt the citizens of occupied France / Poland / Czechoslovakia / Jersey during WW2 had many nuanced things to say about the German occupation forces...

Towards the end, the story loses drive a little bit. Events speed up radically, to the point of becoming a little confusing. At one point, I really struggled to understand whether I was reading the framing narrative or the life story narrative. The ending feels rushed, as if the author had grown tired of the book and just wanted to get it out of the way. Or, perhaps, as if it received less editorial TLC than the start of the book.

For me, the most problematic aspect of the book lay in its gender politics. I have not read (m)any novels written by Arab authors. I tried reading one (HWJN), but gave up on it, due to problematic gender politics in that novel.

For most of its length, Vanished treats female characters as any other novel would. I can't really discuss the problematic aspects, but I do know that any feminist friends of mine would read certain elements with their teeth very firmly clenched, and even I felt quite uncomfortable.

Vanished does a good job of being entertaining. It is educational in the way it depicts Palestinian society, though very simplistic beyond that microcosm (Israel BAD, Palestinians OPPRESSED). It's worth a read for anyone who wants to know what living in Gaza must have been like in the recent past.

Rating: 3.5/5

PS: For a very nuanced, intelligent and nevertheless thrilling and exciting novel handling the effects of oppression on oppressors and oppressees alike, I would heartily recommend Kindred. Perhaps such things can only be written about with such masterful nuance a hundred years after the fact...

Showing posts with label current affairs. Show all posts

Showing posts with label current affairs. Show all posts

Tuesday, 14 June 2016

Sunday, 5 June 2016

Losing Israel by Jasmine Donahaye

A few weeks ago, the shortlist for the Wales Book of the Year Award was announced, alongside the public vote for the 'People's Choice Award'. Among the shortlisted books, the title Losing Israel grabbed my attention (despite the rather bland cover image).

I make no secret of the fact that I'm a member of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign, so naturally I take an interest when a book about Israel is in with a shot at a literary award in my own backyard.

Here's the book's cover synopsis / blurb:

Losing Israel required a bigger gear shift than the other non-fiction books I've read: I found it very slow to begin with. The best nonfiction hooks you from the first page - like The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons, and good travel writing usually lures you in with an intriguing, evocative start (e.g. the Wales Book of the Year Award winner Cloud Road, which then lost a lot of the momentum of the start of the narrative). Losing Israel, on the other hand, has a very slow, meandering beginning. The first quarter of the book is not very engrossing, which does not bode well for its chances at finding a large audience.

Once I got used to the nonlinear, meandering literary rambles, the book did become interesting. It never really moves beyond the cover blurb in terms of events, so whether you find it absorbing will rely heavily on how interested you are in getting a glimpse of another person's life and views. I would recommend the book to other people who have never themselves been to Israel or the Palestinian territories, but who want to understand the issues that cause the conflict in that area, and to readers wishing to glimpse the conflict through the eyes of a liberal Jewish Israeli Expat.

The book also stands out because it isn't biased and one-sided, unlike most things written about Israel and Palestine. Jasmine Donahaye interrogates the history of Israel through the microscopic perspective of her own family history, and then maps that onto the larger history. She goes out of her way to find truth and reality, and wrote as truthful a book as she could. However, it is very much a book about the past, with comparatively little interest in the present, and virtually no interest at all in the future. It's good background reading, but won't help anyone trying to imagine a different future for Israel or the Palestinians, and to me, that was a little disappointing.

Rating: 3.5/5

The book is a story of a woman trying to find herself, to gain an understanding of the history that shaped her, her mother, and the way her family shaped the history of a land she'd loved and worshipped. There's quite a lot of navel-gazing introspection, a heavy dose of Weltschmerz, a great dollop of uncertainty.

Finally, towards the very end, Jasmine Haye seems to be making her uncomfortable peace with Israel:

The world needs people to care, to talk, to speak out. It needs people who can see different sides (as the author does) and who can advocate for empathy and justice and decency. I was initially quite excited about the book, hoping that it might be a useful one to recommend to people as a nuanced, truthful and worthwhile introduction to the Israel / Palestine issues. And the book is nuanced, truthful and worthwhile about the events of 1948. So it's a shame that it ends with more introspection, with wallowing, seemingly without any desire to work towards any change. Does Jasmine Donahaye join Jewish Voice for Peace? Does she share the work of Breaking the Silence? Does she take any interest in the present and the future? (In the postscript she talks about "another war between Israel and Hamas", which suggests not: it's the Israeli government's narrative that it is fighting "Hamas". It uses the phrase "Hamas" the way the author's racist aunt uses the word "Arabs". Israel does not fight Hamas, it fights Palestinians. As even-handed as her take on the past is, the book doesn't suggest she takes any strong interest in the present.) The book makes it seem as if all she really got for her research were mixed feelings about the past, rather than any drive to try and fix the broken land of Israel and Palestine, and that is heartbreaking. What good is shame, if one does not take any action as a result?

And, to be honest, I'd hoped for a more accessible text, too. The book, written for a Welsh audience, uses the Welsh word hiraeth a few times - as a non-Welsh person, I know it's a unique word in the Welsh language, without a direct English equivalent. This, I guess, limits who the book it is written for. It's written for the Welsh literati. It's not written for Israelis or Palestinians. It's not written for Joe Public in the UK or America, or for politicians and leaders. I had hoped this book would be great to make people think, perhaps re-evaluate and change their minds, but, with its niche audience, I fear that it will struggle to get enough readers to make much of a difference.

There is a lot to like about the way the book handles history, but I, personally, did not like the way the book sees the present or the future. History is there to be learnt from, not to be discovered and filed away.

I make no secret of the fact that I'm a member of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign, so naturally I take an interest when a book about Israel is in with a shot at a literary award in my own backyard.

Here's the book's cover synopsis / blurb:

"During a phone call to her mother Jasmine Donahaye stumbled upon the collusion of her kibbutz family in the displacement of Palestinians in 1948 - and earlier, in the 1930s. She set out to learn the facts behind this revelation, and her discoveries challenged everything she thought she knew about the country and her family, transforming her understanding of Israel, and of herself.It's a promising description, as it offers a personal perspective of a complex situation. When I started reading, however, I very quickly found myself far away from my usual reading habits. As you might expect from a reader primarily interested in science fiction and fantasy, I enjoy stories with a plot and some exciting premise that takes me away from the everyday world. I do read occasional literary fiction and, less frequently, non-fiction books, but they often require a change of mental gears.

In a moving and honest account that spans travel writing, nature writing and memoir, Losing Israel explores the powerful attachments people have to place and to contested national stories. "

Losing Israel required a bigger gear shift than the other non-fiction books I've read: I found it very slow to begin with. The best nonfiction hooks you from the first page - like The Tale of the Dueling Neurosurgeons, and good travel writing usually lures you in with an intriguing, evocative start (e.g. the Wales Book of the Year Award winner Cloud Road, which then lost a lot of the momentum of the start of the narrative). Losing Israel, on the other hand, has a very slow, meandering beginning. The first quarter of the book is not very engrossing, which does not bode well for its chances at finding a large audience.

Once I got used to the nonlinear, meandering literary rambles, the book did become interesting. It never really moves beyond the cover blurb in terms of events, so whether you find it absorbing will rely heavily on how interested you are in getting a glimpse of another person's life and views. I would recommend the book to other people who have never themselves been to Israel or the Palestinian territories, but who want to understand the issues that cause the conflict in that area, and to readers wishing to glimpse the conflict through the eyes of a liberal Jewish Israeli Expat.

The book also stands out because it isn't biased and one-sided, unlike most things written about Israel and Palestine. Jasmine Donahaye interrogates the history of Israel through the microscopic perspective of her own family history, and then maps that onto the larger history. She goes out of her way to find truth and reality, and wrote as truthful a book as she could. However, it is very much a book about the past, with comparatively little interest in the present, and virtually no interest at all in the future. It's good background reading, but won't help anyone trying to imagine a different future for Israel or the Palestinians, and to me, that was a little disappointing.

Rating: 3.5/5

Commentary / Spoilers / Arguing with the text

I'm not sure whether a Spoiler Warning is necessary for literary non-fiction, but I felt a desire to discuss aspects of the book in more detail, or rather, to argue with the text. I think as a reader, I would not have wanted to know more than the back cover already reveals about the book's events, so: SPOILER WARNING for the rest of this blog post / review. I would only recommend reading the rest if you've already read Losing Israel.

One thing that struck me is that Jasmine Donahaye's ignorance of Israel's history was not wholly due to indoctrination and selective information. The blurb and the book present her realisation of a gap in her own narrative of Israel as an awakening, an accidental epiphany, triggered by a phone conversation with her mother. I'm sure that's true, but when you read the book, it also becomes clear that this revelation only really sank in because of the particular timing of that conversation.

There is a fascinating article about advertising, of all things, which relates to this: "How Target Figured Out a Teen Girl Was Pregnant Before Her Father Did". The article explains how researchers have found that humans become creatures of habit, including their consumer behaviour. The habits become so strong that it's very, very hard for advertisers to effect any changes. However, during certain periods when we go through big life changes, humans suddenly become incredibly flexible. All their habits are suddenly fluid and up for grabs. Getting married, having children, getting divorced, leaving university, starting university, moving to a new city, getting or losing a job. It seems self-evident that all of these would involve some changes, but on a purely intuitive level, you might wonder why, say, your shampoo or toothpaste brand choices should become more flexible just because you happen to have graduated from university. Advertisers don't care about the reasons, what they care about is the opportunity, and in this case, one particular period of pattern fluidity turned out to be identifiable to a chain of shops based on the things people bought using the reward cards - and once identified, those shoppers were targeted with extra and personalised advertising to tap into this flexibility.

Jasmine Donahaye had the conversation with her mother shortly after a tragic bereavement - her sister had died from cancer, not having told Jasmine about her illness until a few days before her death. Following on from these devastating developments, the author was clearly in one of those periods of being shaken and suddenly fluid and flexible in all aspects of her life. So, when a phone conversation turned to her grandfather's scars and her mother mentioned "villagers" and "Arabs" who probably caused the scars, her brain just happened to be receptive to change, and she suddenly found herself asking "what villagers?" because she did not know of any Arab villages near her grandfather's kibbutz...

She does mention the massacre at Deir Yassin, and a wider awareness of the Nakba:

"What I knew about the Nakba I knew in a broad, general sense. Even though I had learned a little bit about this other history, about people fleeing their homes in fear, I knew and didn’t know, just as many Jews, many Israelis, deliberately or otherwise, know and don’t know. The details of who and how and where are passed over or sidelined in the ongoing argument about why people left, about what created the Palestinian refugee ‘problem’. There are exceptions, like the massacre at Deir Yassin, although I had never heard of Deir Yassin as a child or a teenager. In many ways it is the argument over such extreme cases that has allowed the particular stories elsewhere to be lost in the broad generality of the term ‘Nakba’ or the ‘War of Independence’.

(...)

When, earlier, I had learned in a general sense about Palestinian Arabs fleeing the threat of war and then fleeing war, about villages being destroyed to prevent their return, and to erase their memory, I had been outraged, and am still outraged. Nevertheless, there was always something detached about my reaction; it was always an outrage that had happened somewhere else. But here it was close to home, not in the abstract: here it was near Beit Hashita, in the place my mother came from. What had happened there? How had it happened – and how was it that I could not have known? All the many times I’d visited the kibbutz, all the long weeks and months I’d spent there, nobody had ever mentioned the villages. I’d never heard them spoken about, never heard the story told – and hearing nothing, knowing nothing, I’d never had a reason to ask. "...and this is where I simply cannot agree with the author. To say she'd "never had a reason to ask" is not quite right. To know about a massacre and ethnic cleansing, and about outrageous deeds committed by one's country is a reason to either ask, or at least to not treat it as "abstract" and something "that had happened somewhere else". It seems to me that her ignorance prior to the period she describes in this memoir was not purely other people's fault: not to interrogate the past had simply been her routine, and when her sister died, that routine collapsed, became fluid, and she suddenly became open to a radically different view of her own family history.

The book is a story of a woman trying to find herself, to gain an understanding of the history that shaped her, her mother, and the way her family shaped the history of a land she'd loved and worshipped. There's quite a lot of navel-gazing introspection, a heavy dose of Weltschmerz, a great dollop of uncertainty.

On the one hand, I want to applaud the author for bothering. Her efforts to seek out Palestinians, Arabs and their views are commendable. Going through a reassessment of one's sense of belonging must have been traumatic. And I also want to applaud her braveness for daring to write about a topic that frequently results in bullying and hate campaigns against anyone who dares to say anything at all.

However, having found her world view changed, it's disappointing that she does not seem interested in taking much action to affect the world in turn. The very existence of the book is clearly an achievement, and months of work must have gone into it, but I can't help wondering, is that it? Will she be sending a copy to the racist aunt whose deeply racist proclamations about Arabs and Africans she did not dare challenge at the time due to being a guest and bound by the rules of hospitality? Probably not.

"What can I say to Myriam? I know that if I were to describe the hospitality I received from Abu Omar, from Randa and Ghaith, she would surely say, as she said about the man who changed my tyre the previous year, ‘Nu, so there are some good Arabs.’ It would not affect her feelings about the undifferentiated mass of ‘the Arabs’. What I am doing and where I have been travelling is a provocation to her – and it is therefore harder, and it costs more for her to offer me hospitality than for me to accept it. She welcomes me into her home despite what she herself is appalled by in me, despite what I am doing, which to her is treacherous and dangerous. She must be raw with aggravation, but she does not tell me to go and never come back – I am family. She welcomes me because hospitality is, to her, something unbreakable. Also, I realise, quite suddenly, quite unexpectedly, that she loves me. I watch her, sitting exhausted and shrunk in the huge chair, with her tired, angry face, and she looks up at me and gives me her ironic, lopsided smile and that ineffable Israeli shrug, and the breach, the gulf, is sealed up, and none of it matters, because I love her too."

Having just searched for the name Myriam in my Kindle edition, about half the instances of the name ask "What can I say to Myriam", and in the end, the author never says anything. This, the end of a chapter and final appearance of Myriam, shows the exact thing I found so frustrating: an unwillingness to challenge the darkness, and an overly conciliatory attitude: that sense that Myriam must be even more appalled by Jasmine's actions than Jasmine is by Myriam's attitudes, so therefore, despite their differences, everything is somehow alright, and family ties and love matter more than right and wrong. This is simply not a perspective I can sympathise with.

Finally, towards the very end, Jasmine Haye seems to be making her uncomfortable peace with Israel:

"It is a bad sign, I think, if I can begin to use the word Palestine without discomfort and uncertainty. None of the approximations or conjoined names that attempt to repudiate that future deliberate amnesia are satisfactory – 'Israel/Palestine' or 'Israel-Palestine', or their reverse. Better that the name Palestine remain bulbous and burgeoning with ambiguity; better that the landscape remain complex and difficult; better that I hesitate between naming this tiny iridescent bird an orange-tufted sunbird, or a Palestine sunbird."

(...)

"My country Israel is leaving me too, but not 'into the hands and possession of another country and another civilization', as J.R. Jones saw the predicament of Wales, and as is the predicament of Palestine. My country is leaving me because its story is ceasing to exist, and because of what it has strangled out of existence. I grieve the loss, I grieve its departure from me, but it’s a grief coloured darkly by shame."

(...)These three passages struck an unhappy chord for me. I am glad the author expended the energy to look into Israel's history, and her own family history. I am very glad that her certainty in the Goodness of Israel has been shaken, that she has grown sympathetic to the Palestinians' perspective. But the world does not need her to feel "discomfort" about terminology. The world does not need her to grieve for an Israel that never really was real, or to wallow in shame. Neither does it matter whether she feels a need to love the place, tainted though it may be.

"Love of a person, of a place – the more you know, the more complicated it is. The knowledge that the person is wounded, that the place is stained doesn't diminish your love. The person and the place matter less, perhaps, than your need to love,"

The world needs people to care, to talk, to speak out. It needs people who can see different sides (as the author does) and who can advocate for empathy and justice and decency. I was initially quite excited about the book, hoping that it might be a useful one to recommend to people as a nuanced, truthful and worthwhile introduction to the Israel / Palestine issues. And the book is nuanced, truthful and worthwhile about the events of 1948. So it's a shame that it ends with more introspection, with wallowing, seemingly without any desire to work towards any change. Does Jasmine Donahaye join Jewish Voice for Peace? Does she share the work of Breaking the Silence? Does she take any interest in the present and the future? (In the postscript she talks about "another war between Israel and Hamas", which suggests not: it's the Israeli government's narrative that it is fighting "Hamas". It uses the phrase "Hamas" the way the author's racist aunt uses the word "Arabs". Israel does not fight Hamas, it fights Palestinians. As even-handed as her take on the past is, the book doesn't suggest she takes any strong interest in the present.) The book makes it seem as if all she really got for her research were mixed feelings about the past, rather than any drive to try and fix the broken land of Israel and Palestine, and that is heartbreaking. What good is shame, if one does not take any action as a result?

And, to be honest, I'd hoped for a more accessible text, too. The book, written for a Welsh audience, uses the Welsh word hiraeth a few times - as a non-Welsh person, I know it's a unique word in the Welsh language, without a direct English equivalent. This, I guess, limits who the book it is written for. It's written for the Welsh literati. It's not written for Israelis or Palestinians. It's not written for Joe Public in the UK or America, or for politicians and leaders. I had hoped this book would be great to make people think, perhaps re-evaluate and change their minds, but, with its niche audience, I fear that it will struggle to get enough readers to make much of a difference.

There is a lot to like about the way the book handles history, but I, personally, did not like the way the book sees the present or the future. History is there to be learnt from, not to be discovered and filed away.

Tuesday, 1 December 2015

Off-Topic Post: Thoughts about Paris and Syria

Paris

Let's start with the obvious. The attacks in Paris were reprehensible atrocities, committed by despicable human beings. Nonetheless, something rang hollow about the news coverage and all the statements issued by politicians in the aftermath.The more I thought about it, the more I realised that what rang so hollow was the outrage. The bereaved, the survivors - they have every right to be aggrieved and outraged. But, politicians? European leaders? Hollande, Cameron? Newspapers like the Daily Vile and The Scum?

It's not just disgusting how media (and politicians whose career is built on hatred and bigotry) instantly began to speculate (cough, assert, cough) that the attackers must have come to France among refugees, although that is certainly the most disgusting aspect of the popular outrage being peddled at the time. No, what felt really hollow and wrong is how different the reactions were compared to the reactions when atrocities happen elsewhere.

Worse, there is an outright taboo on saying, writing or thinking something that's very, very obvious, and very very true: the attacks did not come out of nowhere. They were not unprovoked. The murderers are guilty of committing the bloodshed, but Francois Hollande's government shares some responsibility for the attacks on Paris, just as Tony Blair is responsible for the 7/7 attacks on London. Yet to say both these things is taboo among leaders and politicians.

Let's take a step back. If I am saying something taboo, let's work out the logic of that statement. Let's play devil's advocate.

Our governments keep telling we're at war. We're not currently at war with Iraq, but we're at war with Islamic State, at war with Terror, at war with Drugs. But these wars are not like other wars in the distant past: they are certainly not wars where governments face other nation states with similar weaponry and similar might. Instead, stealth aircraft and drones do violence to targets below while being almost untouchable. So modern wars cost us nothing more than money, while whoever we're at war with does all the bleeding. We've become quite comfortable with that. So comfortable, in fact, that there is outrage when the people we are bombing have the audacity to fight back. There's something almost collectively sadistic about this - like a head teacher beating a pupil and expecting to be thanked, not hated, for the violence they dish out.

Now, the attacks in Paris were mass slaughter of civilians. That's not self defence - to us. But, for a crazy moment, let's think ourselves into the enemy's shoes. Drones and stealth aircraft are untouchable. Armies and soldiers are well defended and have overwhelming force. (Not that the reaction over here is any different when a soldier is killed when he's defenceless). So how to fight an invincible enemy? Is it really a surprise they target civilians? Isn't it, in fact, a logical conclusion of our nations being at war with them? Have Islamic State signed up to the Geneva Convention, international treaties on human rights, etc.? No, of course not. They don't believe in human rights for the people they claim to rule, so why would they have any more respect for Westerners' rights? How can our leaders feign surprise and outrage when enemies defend themselves, and don't play by our rules?

I use the words 'defend themselves' intentionally: it does not imply victimhood or blamelessness. When Britain declared war on Germany, they did not expect the Nazis to just take their lumps and not fight back. Any war is a two-way street of violence. To expect anything less is unreasonable.

The attacks on Paris were a logical and likely outcome of France's involvement in the fight against Islamic State / terror.. That doesn't make them less atrocious and vile, it does not absolve the attackers of blame, It simply means that France's politicians are partially responsible for them, and that all their outrage is hypocritical.

Islamic State

Every indication is that Islamic State is, essentially, a death cult. There are only two things they appear competent at: getting publicity and inflicting suffering.Obsessed with violence and death, fuelled by hatred, vanity and insanity, they are filled with self-destructive urges. Their glossy magazine celebrates the gory photos of their dead fighters as much as it celebrates the violence they inflict on others. Islamic State is to Islam what the Lord's Resistance Army in Uganda are to Christianity. As such, they are dangerous, sick, and it's pretty obvious the world would be a better and safer place without them.

I don't know enough about the Lord's Resistance Army (beyond their use of child soldiers and their mass abductions etc.), but it seems to me that the totally batshit crazy psycho cults out there (central American drug cartels, LRA, ISIS) have some things in common. According to some, much of ISIS was moulded into shape by going through a joint experience of suffering - being locked into an American prison camp - and used the resentment at their mistreatment to fuel a rage that would ultimately lead to IS. Similarly, drug cartel violence seems to be on an escalating cycle, which was only fuelled, not extinguished, by the War on Drugs and its more violent interludes and phases.

Basically, violence and abuse seem to create insanity, rage, revenge, more violence and worse abuse. I shudder to think what the populations currently under ISIS' gruesome rule might one day retaliate as.

At the same time, ISIS and drug cartels have other commonalities: ultimately, they are psycho creeps with guns. Do they have an armed vehicle or two, maybe some missiles? Sure. But when it comes down to it, all they need to be sources of terror is guns and swords. The Rwandan genocide was largely carried out by people with machetes - all it takes for genocide to happen is people willing to commit it, and relatively light weaponry against a comparatively unarmed population.

What good are drones, missiles and bombs against widely dispersed psychos with guns?

Syria

Syria has become a battleground for every nation with aspirations at exerting power in the Middle East. It's a tragedy of unimaginable proportions. Here's a history of events since the Arab Spring:If you were a person living in Syria, what would you do? If you were a parent in Syria, which faction would you turn to? From outside, it does not look as if any of the armed factions are 'the good guys'. Being a civilian / unarmed person in Syria must be terrifying.

Bombing ISIS

Reading all the above, you might conclude that I am dead against bombing IS in Syria, or bombing Syria. I wish I could be that categorical. I am doubtful that bombing will have any positive effect. In fact, it seems to me it will only feed the cycle of violence, and has no way of replacing a mess with something good.At the same time, the atrocities committed by IS are such that I can't be entirely opposed to our governments trying to get rid of them. Clearly, anything would be better than that lot. Well, anything except Assad's regime, maybe.

I do believe that voting to bomb IS effectively means voting for IS to retaliate against British civilians. The UK government has already joined the fight against IS in Iraq, so from that point of view, they have already voted to make the civilian population in the UK a target for more attacks by IS sympathisers. Expanding to Syria just makes us a bigger target. That isn't necessarily a reason to vote against intervention - if the UK could make a difference & genuinely improve matters, then some innocent British lives may be a fair price to pay for saving thousands of innocent lives in Syria. But can the UK make such a difference?

If the Western governments have a good, realistic, achievable plan (hah!) for how IS can be defeated, and Assad removed, and peace and stability brought to Syria, then I wouldn't be opposed to war / force being involved. Unfortunately, there is no indication that any plan, let alone a good one, exists.

Things Our Governments Should Do Instead

Here's a TED Talk:It seems to me that there are much more effective things the UK and Europe (and America) could do than throwing more bombs and death into the Middle East. The first and foremost of these is to help people who have been fleeing from the chaos and violence.

Now, personally, I am not opposed to opening borders and letting them in, but I understand that there is significant popular resistance to that approach in most European nations. So, short of helping everyone fleeing the chaos and death to Europe, there are still things our governments can and should do.

1) Fund Refugee Cities, not Camps

Refugees who have fled the violence live in tent cities, in a permanent limbo. The UN, to some extent, looks after them, but they are critically underfunded and unable to offer people anything but the barest minimum of life support. Having millions of people live in poverty, with nothing to do, is a recipe for disaster. It's a recipe for letting people stew in their trauma, their anger at their misfortunes, and ultimately, it could be a recipe for turning people into our enemies because we did not help out when they desperately needed it. At best, it turns them into enemies of other Syrians, and ensures that grievances can fester and conflicts continue for more generations to come..

In this video, a Swedish economist points out that we spend £50 a day on refugees who make it to Europe, but only £1 a day on refugees who are stuck in Lebanon or Jordan.

Hans Rosling on the refugee crisis

Europe is getting its response to the refugee crisis all wrong. That’s the view of Professor Hans Rosling of Gapminder – watch him explain why.

Posted by Channel 4 News on Tuesday, 24 November 2015

It's perfectly within the powers of our government to spend more. It's overdue. Let's treat the Syrian diaspora the way we'd treat cities flattened by tsunamis, earthquakes, volcanoes and hurricanes. Let's pump in billions, and fund the building of permanent, viable cities. Let the refugees build their own futures - give them materials, work and opportunities and a sense of a sustainable future, and a chance to live, rather than expecting them to rot in limbo and stay there.

Also, from a purely strategic point of view, wouldn't it make sense to start building a (municipal) government from the ground (& grassroots) up, in those refugee camps? Perhaps a viable Syrian government-in-exile can grow, and learn the art of governing, co-existing, self-policing and, ultimately, once the bloodletting in Syria itself fizzles out, be in a position to help Syria reunite and heal? Where are Syria's future rulers supposed to arise from? Armed militias? How would that be any better than Assad's regime?

2) Strangle the Arms Trade

Where do the various factions get their guns & ammo from? Shockingly, the answer is "pretty much everyone". (This 2013 article precedes much of the rise of IS).

As long as arms are freely flowing into Syria (and Northern Iraq), and as long as every other nation with aspirations to exert control in the region keeps running a proxy war, the bloodletting won't stop, the trauma will continue, and we can only create more enemies.

3) Come up with a f***ing plan

Seriously, is "let's throw bombs on it" the only answer our governments can think of? Is this a matter of "if the only tool you have is a hammer, treat everything as if it were a nail"?

HOW COME BOMBS ARE OUR GOVERNMENTS' ONLY TOOLS?!?

I mean, seriously, WTF?

Syria should be under a complete UN arms embargo. There shouldn't be efforts to get more nations to pile on and add bombs to the fire. All efforts should be towards getting Iran, Saudi Arabia, Russia and the rest (including Western governments) to step back and take their military support with them.

Where are the diplomatic efforts to disengage all the proxy powers?

And where are the efforts for planning for a post-civil-war future? The trauma inflicted by this conflict will last for decades, even generations. What planning is there for overcoming that? Where are our governments' plans for preventing another Taliban, another ISIS, another Al Queda from forming ten, twenty years from now, from the ashes of this conflict (even if IS and Assad are defeated / erased)? If we want to defeat IS and Assad and fix Syria, how come our plan appears to be "let's bomb them and expect them to be grateful for our benevolent bombings"?

4) Anyhow

I'm glad Jeremy Corbyn is giving his MPs a free vote. I'm not in support of bombing IS in Syria, but I'm not opposed enough to join a Stop The War Coalition protest.

I just really wish our governments came up with complex answers to complex problems, rather than opting to try for simple solutions which don't stand much chance of fixing anything.

(For the record: I was in favour of intervention in Kosovo, moderately against intervention in Afghanistan, very strongly against the 2003 Iraq war, undecided about intervention in Libya, and I am moderately against intervention in Syria at this time)

Saturday, 17 October 2015

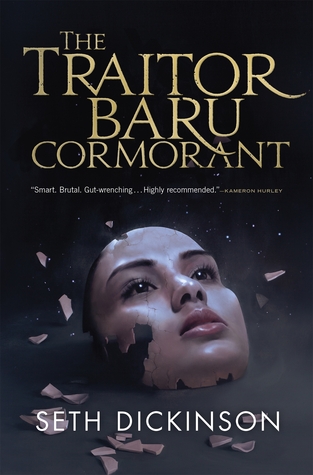

The Traitor by Seth Dickinson

The Traitor (also sold as The Traitor Baru Cormorant) is a unique novel, quite unlike anything I've ever read before. That alone earns it a lot of respect from me. It's also intelligent, thoughtful, strategic, all without ever forgetting about character complexity.

The Traitor starts when Baru Cormorant is a girl, watching sails in the distance. She is aware that her parents are troubled: Empire is at their doorstep, and they fear their civilization and culture is about to be subsumed. Baru has mixed feelings: there is something exciting about these ships, these foreign traders, and their spectacle and overwhelming power. Soon, she is recruited into their special school, destined to become one of the first of her people to absorb the Empire's culture fully. Then, a small skirmish with a neighbouring tribe turns into all-out war as the Empire 'supports' their allies with an army, and one of Baru's fathers dies. Her mother tells her foul play was at work: the Empire murdered him because he was in a family unit that was not monogamous. Some years later, the Empire's treatment of homosexuals becomes an urgent problem for Baru.

Baru Cormorant decides that the Empire is too big, too powerful to defeat by (her mother's dreams of) rebellion. She throws herself ever more deeply into her studies in order to rise to the very top and change the empire itself. The novel tells the story of her rise, her assignment, her betrayals...

The Traitor Baru Cormorant is not an epic fantasy novel in the traditional sense. No orcs, no dragons, no elves, no monsters, no magic. In fact, it is more akin to an alternative Earth, with alternative human cultures. Some names echo names on Earth: there are several cultures whose naming conventions appear to be Latin American, African, Polynesian, etc.

Baru Cormorant is not a traditional hero. She might leave her family behind, but she does not have a benevolent mentor. She has grand designs and dreams and wants to change the hostile world, but she does not do so through being a chosen one heading into battle on the back of a prophecy. You could argue that she is a chosen one, but she is chosen for her mind and her skill, called a savant. She is not chosen by her people or the good guys; she is chosen by the Empire.

Perhaps most importantly of all, Baru does not pursue a path of heroism and binary good/bad, does not fight the empire from outside in futile rebellion. Instead, she uses realpolitik, manoeuvring the politics of power in a way that Tywin Lannister would be proud of. She acts utterly ruthless, even if she suffers internally.

Baru Cormorant is a striking, memorable hero. I don't recall ever coming across a character like this - hard, strong, a stone cold operator, willing to do terrible things in the short term in service to her longer term goals. Not since watching the documentary 'The Fog of War' have I come across a personal conflict like that, and I struggle to think of any instance when such conflict occurred in books I've read. A Song of Ice and Fire, for example, may be full of politics and battle and betrayal, full of power struggles, but in comparison with Baru Cormorant, no character or family comes close in complexity. Song of Ice and Fire has good guys and bad guys, well-intended roads to hell (Daenerys, John Snow) and degrees of badness (Jamie Lannister, Stannis Baratheon). Baru Cormorant is so much more complex because she does terrible things, knowing they are terrible, internalising her regret and guilt. She'd not a baddie nor a hero.

There is a whole lot more to the novel, beyond complex characters. An ultra-conservative empire, obsessed with eugenics and family values / 'social hygiene' but technologically advanced and, at least at the level of middle management, meritocratic. It's improving people's living standards, quality of life, life expectancy (unless you fall foul of their moral barometer), spreading through trade and capitalism and banking... while local cultures of diversity, minority faiths, non-nuclear families and sexually liberal attitudes get absorbed and destroyed. The book has geopolitics that do not match or even closely mimic our own, but take different aspects and play around with them. Falcrest acts like modern America / China, with the social mores of Nazi Germany and Saudi Arabia. You can read it in a dozen different ways, but it's a chilling adversary to encounter in a novel.

Similarly, there is a lot in the book about the workings of power, the difference between the power people see and power as it really works. In fact, even though it must have written well before the #piggate affair, The Traitor's circles of power work exactly as described in 'The PM, the Pig and Musings of Power'. The parallels between novel and real events are so striking that I cannot help feeling a chill at how insightful, intelligent and authentic this novel really is.

I will admit that it lost some momentum in the second half, but it makes up for that with an utterly relentless finale. Highly recommended if you're looking for a very smart, complex and entertaining read.

Rating: 5/5

The Traitor starts when Baru Cormorant is a girl, watching sails in the distance. She is aware that her parents are troubled: Empire is at their doorstep, and they fear their civilization and culture is about to be subsumed. Baru has mixed feelings: there is something exciting about these ships, these foreign traders, and their spectacle and overwhelming power. Soon, she is recruited into their special school, destined to become one of the first of her people to absorb the Empire's culture fully. Then, a small skirmish with a neighbouring tribe turns into all-out war as the Empire 'supports' their allies with an army, and one of Baru's fathers dies. Her mother tells her foul play was at work: the Empire murdered him because he was in a family unit that was not monogamous. Some years later, the Empire's treatment of homosexuals becomes an urgent problem for Baru.

Baru Cormorant decides that the Empire is too big, too powerful to defeat by (her mother's dreams of) rebellion. She throws herself ever more deeply into her studies in order to rise to the very top and change the empire itself. The novel tells the story of her rise, her assignment, her betrayals...

The Traitor Baru Cormorant is not an epic fantasy novel in the traditional sense. No orcs, no dragons, no elves, no monsters, no magic. In fact, it is more akin to an alternative Earth, with alternative human cultures. Some names echo names on Earth: there are several cultures whose naming conventions appear to be Latin American, African, Polynesian, etc.

Baru Cormorant is not a traditional hero. She might leave her family behind, but she does not have a benevolent mentor. She has grand designs and dreams and wants to change the hostile world, but she does not do so through being a chosen one heading into battle on the back of a prophecy. You could argue that she is a chosen one, but she is chosen for her mind and her skill, called a savant. She is not chosen by her people or the good guys; she is chosen by the Empire.

Perhaps most importantly of all, Baru does not pursue a path of heroism and binary good/bad, does not fight the empire from outside in futile rebellion. Instead, she uses realpolitik, manoeuvring the politics of power in a way that Tywin Lannister would be proud of. She acts utterly ruthless, even if she suffers internally.

Baru Cormorant is a striking, memorable hero. I don't recall ever coming across a character like this - hard, strong, a stone cold operator, willing to do terrible things in the short term in service to her longer term goals. Not since watching the documentary 'The Fog of War' have I come across a personal conflict like that, and I struggle to think of any instance when such conflict occurred in books I've read. A Song of Ice and Fire, for example, may be full of politics and battle and betrayal, full of power struggles, but in comparison with Baru Cormorant, no character or family comes close in complexity. Song of Ice and Fire has good guys and bad guys, well-intended roads to hell (Daenerys, John Snow) and degrees of badness (Jamie Lannister, Stannis Baratheon). Baru Cormorant is so much more complex because she does terrible things, knowing they are terrible, internalising her regret and guilt. She'd not a baddie nor a hero.

There is a whole lot more to the novel, beyond complex characters. An ultra-conservative empire, obsessed with eugenics and family values / 'social hygiene' but technologically advanced and, at least at the level of middle management, meritocratic. It's improving people's living standards, quality of life, life expectancy (unless you fall foul of their moral barometer), spreading through trade and capitalism and banking... while local cultures of diversity, minority faiths, non-nuclear families and sexually liberal attitudes get absorbed and destroyed. The book has geopolitics that do not match or even closely mimic our own, but take different aspects and play around with them. Falcrest acts like modern America / China, with the social mores of Nazi Germany and Saudi Arabia. You can read it in a dozen different ways, but it's a chilling adversary to encounter in a novel.

Similarly, there is a lot in the book about the workings of power, the difference between the power people see and power as it really works. In fact, even though it must have written well before the #piggate affair, The Traitor's circles of power work exactly as described in 'The PM, the Pig and Musings of Power'. The parallels between novel and real events are so striking that I cannot help feeling a chill at how insightful, intelligent and authentic this novel really is.

I will admit that it lost some momentum in the second half, but it makes up for that with an utterly relentless finale. Highly recommended if you're looking for a very smart, complex and entertaining read.

Rating: 5/5

Friday, 5 December 2014

A brief interruption for some current affairs pondering

A brief interruption for some current affairs pondering

I started this blog by copying lots of the reviews I write on Goodreads into blogger. I wanted it to be a book blog, with minimal or no other things. Reviews, reviews and nothing but reviews.

But if I'm publishing a blog anyway, sometimes the need to think aloud, or even rant, might be too hard to resist. So I guess be warned: it could happen in future.

It's happening today.

Unarmed black people being killed by police in the USA (and the police getting away with it) has been a very unhappy theme this week. It's horrible. Race has become a big issue again, and it is absolutely right that people talk and think about race, and justice.

It's also right that not everyone will have the same opinions and thoughts about everything, and I decided to do some thinking below.

The Shooting of Michael Brown

I tend to get most of my news from the BBC, so here's a summary of the testimonies and different narratives about the shooting which I read: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-30189966

Of course, the testimonies don't agree about every aspect, but there are some things that seem to be fairly incontrovertible:

- Michael Brown stole something from a convenience store, became physical with the shop owner, and left with a friend.

- The police officer drove past the two young men and told them off for walking in the street.

- Shortly thereafter, the convenience store theft was reported on the police radio, and the police officer drove back to confront the teenagers.

- A physical confrontation occurred: the police officer inside the car, Michael Brown outside, the window open.

- Accounts vary: The door was either aggressively slammed into Michael Brown or Michael Brown intentionally tried to block it from opening. There was some pulling and pushing through the open window.

- The police officer shot Michael Brown several times through the window.

- Michael Brown and his friend ran away.

- The police officer, gun drawn, pursued them.

- Michael Brown turned to face the officer.

- Here, accounts vary: he either raised his hands in surrender or started to run at the police officer.

- He was then shot several more times and died.

Protesters see a martyr in Michael Brown because they choose to believe the version of the story which claims he raised his hands and shouted "Don't shoot" and "I don't have a gun". They raise their hands and see this incident as a clear cut murder, an execution of an unarmed teenager for being black or for having dared to resist a police officer (whilst being black).

Maybe that is what happened; maybe it isn't. I don't think any trial jury would ever have come to that conclusion "beyond reasonable doubt". I certainly wouldn't come to that conclusion at that level of certainty.

But, after all, it wasn't a trial jury, but a Grand Jury that decided not to charge the police officer.

The Grand Jury

This is where this BBC story becomes useful: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-30042638

"The grand jury was deciding whether Officer Wilson should be charged with any one of four possible crimes:

It also had the option of charging the policeman with armed criminal action, if it could prove he was carrying a loaded firearm with the intent to commit a felony.

- first-degree murder (any intentional murder that is willful and premeditated with malice aforethought according to Wikipedia)

- second-degree murder (an intentional murder with malice aforethought, but is not premeditated or planned in advance according to Wikipedia)

- voluntary manslaughter (any intentional killing that involved no prior intent to kill, and which was committed under such circumstances that would "cause a reasonable person to become emotionally or mentally disturbed". Both this and second-degree murder are committed on the spot, but the two differ in the magnitude of the circumstances surrounding the crime. For example, a bar fight that results in death would ordinarily constitute second-degree murder. If that same bar fight stemmed from a discovery of infidelity, however, it may be mitigated to voluntary manslaughter. according to Wikipedia)

- or involuntary manslaughter (stems from a lack of intention to cause death but involving an intentional, or negligent, act leading to death. A drunk driving-related death is typically involuntary manslaughter according to Wikipedia)

Nine out of the 12 members of this jury would have had to vote yes to indict Officer Wilson."

So, how would I have voted?

First-degree murder: No point in charging the officer. The prosecutor would have to prove, beyond reasonable doubt, that the police officer had premeditated the killing – i.e. decided to kill the robber when turning his police car around and driving to him. He'd have to prove that the police officer slammed the door into Michael Brown as an act of aggression, not to get out, but to assault him, and the killing thereafter would have to be a pure execution. I don't think such a version of events would be provable.

Involuntary manslaughter: no point in charging: there was no lack of intention to cause death. A police officer shooting a man in the head twice is clearly intending to kill.

Where things get tricky for me as someone unfamiliar with the legal system is this second degree murder / voluntary manslaughter business. I can understand "intentional killing", but find myself totally uncertain how someone can have "malice aforethought" without it being "premeditated". To my layman's ears, that sounds like a mindboggling contradiction of terms. The notion that a bar fight is somehow less likely to cause a reasonable person to become emotionally disturbed than a declaration of infidelity – that too seems bizarre to me.

Why is there no crime for "intentional killing without malice aforethought or premeditation"? Why is this system assuming that a person either has "malice aforethought" or is "mad with passion" when killing someone on the spot? ("I'm going to take this criminal off the streets" is not exactly malice aforethought...)

Personally, I would have voted that there is a case to answer for either accusation (can jurors vote for each accusation, or do they have only one vote? If only one vote, second degree murder would narrowly win out over involuntary manslaughter in my book).

But, to play devil's advocate, could there ever have been a conviction, beyond reasonable doubt, under either?

Let's have a look at this article: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-28861630

There's a lot that didn't happen. Force continuum? Doesn't sound like it. "You would only use that weapon in a situation where you felt your life or the lives of civilians in the area were in danger." – Arguably, neither was the case, so the police officer very very obviously should not have used his firearm.

But later in the article, there are some sentences about the police training that become worth thinking about:

"When law enforcement officials do shoot, they shoot to kill."

In other words, the decision to kill Michael Brown was effectively made during that scuffle at the car door. The next paragraphs explain how "shoot to wound" would be a very bad idea, and all the training is about shooting to kill, partially in order to make it easier to aim ("aim for centre mass"), and partially to minimise gunplay and end the fight as quickly as possible.

If you train police officers that, once they fire at a suspect, they are supposed to kill them, doesn't that make it more likely that some will keep shooting until the suspect is immobile on the ground?

And then comes the corker: After a police officer shoots someone…

"In the large majority of cases, no charges are brought against the officer. That is in part because in a case of reality versus perception, the police officer gets the benefit of the doubt.

"Maybe he wasn't in danger, but if he reasonably believes he was, he would be justified in shooting," says McCoy (a professor of criminal justice)."

This is where all the testimonies come back in.

The police officer's version of events emphasises his own perceptions – that he was in danger during the scuffle by the car door, that the teenager was very strong, that the teenager was charging at him after the pursuit. Any reasonable person would argue that shooting and killing an unarmed teenager is a disproportionate response to whatever crime he may have committed, and to the resistance and scuffle that occurred. Any reasonable person would agree that a grievous wrong has been done and a tragedy occurred.

But in the context of differing testimonies, and with the way police in America are trained, and considering the police officer only needed to think he was in danger, rather than actually be in danger… I don't think I'd be able to conclude he was "guilty beyond reasonable doubt". And while that, again, is the trial jury's job, not the Grand Jury's, I can imagine members of a Grand Jury thinking along similar lines.

At a Grand Jury, no defence attorneys are present. It's just the prosecutor, the judge and the defendant, and the jury can ask questions. It happens behind closed doors in secret. If I sat on a Grand Jury, and found that the prosecutor did not convince me beyond reasonable doubt that the defendant was guilty, then why would I vote to indict? If the prosecutor can't convince a jury while there is no professional defence present, what would be the point of indicting – the following trial would be sure to fail, end in a "not guilty beyond reasonable doubt" verdict, and waste huge amounts of money.

A lot would ultimately rest on that question: how convincing was the prosecutor, behind closed doors?

It is quite possible that the prosecutor only put in a token effort. [Edited, on 18/12/14: It now looks as if the prosecutor didn't just make a token effort, but went out of his way to present the defendant's case, rather than the prosecuting case, to a point where he included a discredited, white supremacist / fantasist among witnesses. I find myself completely and utterly disgusted and appalled.] It is quite possible that, with nine white jurors and three black ones, inherent racial bias is the reason why they did not indict the police officer. It's even possible that the majority of jurors did vote to indict, but not enough (9/12) to succeed.

Still, without knowing how things played out inside that room, I can imagine scenarios where I would have voted not to indict, even though I absolutely believe that the shooting of Michael Brown was wrong, and not just wrong, but a wrongful act, and very probably a crime, based on the evidence that is in the public domain. I don't believe so beyond reasonable doubt (based on the public domain evidence), and I imagine some of the jurors must be feeling pretty awful about the aftermath. I don't know that they did anything wrong by not indicting that police officer, so I don't feel I can protest about their decision.

(Protesting against police training ideologies and brutality, or for body cameras, however, and I'll happily attend)

The Death of Eric Garner

Compared to the shooting of Michael Brown, the death of Eric Garner has a lot more evidence available, thanks to this video:

Based on the definitions of different crimes earlier in this post, it seems very obvious that what is happening is an involuntary manslaughter.

Of course, the "reasonable doubt" question would arise again – and the fact that Eric Garner was overweight and unhealthy would be exploited by any defence lawyer, and is even being put forward as cause of death by a Republican politician. (Never mind that the coroner ruled it was a homicide: we are conditioned to believe that "fat people die young, of heart attacks", so if a young fat person dies of heart failure, some people will cheerfully disregard the choke hold, the handcuffs, the restraints, and blame the victim's lifestyle exclusively, or at least "reasonably doubt" that the police actions were the cause of death)

Even though I firmly believe that an involuntary manslaughter occurred, I can imagine a jury coming to a "not guilty" verdict because of "reasonable doubts". Therefore, even in this case, I can imagine reasonable people on a Grand Jury choosing not to indict the police officer (although I find it more galling than in the Michael Brown case).

Another thing which is going through my mind is that, in the video, Eric Garner is being restrained a surrounded by half a dozen police officers. Yes, one applied a banned choke hold and then pushed his head against a wall, and that is clearly disgusting. But all the police officers kept him restrained, they all ignored his pleading. They all let him die.

Eric Garner was the victim of an involuntary manslaughter, but the perpetrator was not one police officer; it was all of those present.

(If there's one positive thing about this tragedy that is being revealed about America is that there, citizens can record police actions. In Britain, the guy holding the camera would be arrested immediately and his camera confiscated: they don't let people take photos of, or film, police actions over here)

But was it an avoidable involuntary manslaughter?

Once, I witnessed someone being arrested against his will in Cardiff. The man resisted. The police applied similar levels of force to those in the video. The man started shouting "I can't breathe". The police ignored him. All the bystanders walked past (including myself), no one recorded it. My overwhelming impression was that the police are used to people shouting "I can't breathe" when being forcibly restrained.

There are several possible reasons. Maybe some people lie and shout this as a final form of resistance, or to induce others to record the arrest with a view to using it in their defence or for lawsuits. That would be the most cynical interpretation. Maybe restraining someone against their will is a highly stressful situation: maybe people being arrested in this way frequently suffer panic attacks in the process. Maybe some of the force during the arrest tends to shock the solar plexus and induce cramps in chest muscles, leading to breathing difficulties. The latter two scenarios don't tend to be lethal for healthy strong people if they happen (though they are very traumatic). Maybe it's a combination of these.

My point is: I suspect that police officers are very very used to ignoring pleas of "I can't breathe". I suspect that many police officers routinely assume that all the people who shout "I can't breathe" are lying (the first of the three scenarios I speculated about). That means that it becomes inevitable that some people die while being restrained – because the police probably always ignore it, and they always ignore it because someone, somewhere decided that they can't ever treat it as a medical emergency, or it would be open to exploitation. So it may have been an unavoidable involuntary manslaughter. It's certainly not the first time a black man has agonisingly choked to death, surrounded by witnesses, while being restrained by security ‘professionals'. (That UK case did not result in any prosecution either)

None of this makes what happened to Eric Garner right, or even remotely acceptable. But I can understand that even a non-racist jury of reasonable and decent people could come to a "not guilty" verdict, or even a refusal to indict. I find it harder to stomach than in the Michael Brown case, but I can imagine decent people coming to the decisions that both the Grand Juries reached; I cannot know for certain that either jury was made up of decent people, they may have included despicable ones. But I can imagine it, and so I choose not to direct my anger at the juries.

However.

I think the real villain of these cases aren't (necessarily) the jurors, but the systems and policies and practices that are in place in American policing & judiciary.

- Eric Garner clearly posed no danger to anyone. If he has committed an offence (and it is not clear that he has), then nothing about the offence he's accused of warranted a non-consensual, physically violent arrest.

- I believe (non-consensual) arrests should only happen if there is a threat of serious further crimes, a threat of escape after a serious crime, or at the end of an investigation leading to an arrest warrant. Police should not be allowed to arrest people willy-nilly based on nothing but their own testimony, as the police are no more worthy of the public's trust than civilians.

- Michael Brown did not pose a lethal danger to anyone. He was a criminal, there was a cause for arrest (risk of flight and risk of further serious crimes), but he was unarmed.

- Police training should therefore only be allowed the use of firearms if the suspects have a weapon – a firearm or, if they are closer, a knife or baseball bat etc.

- The definition of voluntary manslaughter should explicitly include "lethal defence of self or property against a person posing a non-lethal threat". It's simply ridiculous that white people get to shoot unarmed black people, claim "self defence" and too often get a "not guilty" verdict or no indictment. There has to be a proportionality to any claim of "defence", and there have been too many instances of people using lethal violence in instances that do not warrant it. (lethal self defence against rape is OK in my book, but lethal self defence against a petty thief or someone resisting against being arrested against their will… there should be a defined crime for that!).

- I don't live in America. Those that do, tell me that "race" is still a big issue, that institutionalised racism is still widespread, and I believe that, even if I can't know for certain that it was the deciding factor in either of the cases that have triggered these protests and responses.

- From over here, across the pond, it looks as if one of the biggest reasons for the too-frequent killings of unarmed suspects is that American ideology values (defence of) property over lives. (Police would rather shoot a petty thief than let him escape unpunished, once they have started the chase). Police forces value their need to enforce a decision once made over lives. (It is more important to them to go through with an arrest, once they announced they're arresting someone, than preserving the life of the suspect). If the individual police officers in these cases are not "guilty beyond reasonable doubt" of involuntary manslaughter, then the police forces themselves, their training methods, policies and ideologies are, in my opinion, "guilty beyond reasonable doubt" of fostering a culture that leads to involuntary manslaughters - i.e. the authorities themselves should be prosecuted for corporate manslaughter.

- Grand Juries seem a strange idea. The decision whether to indict or not should be made by a professional, identifiable and accountable person. (A judge, magistrate or whatever). And if a Grand Jury has to be involved, why a 9/12 majority rather than a simple majority? Members of the jury should probably not just include peers of the accused, but also peers of the victim…

- ideally, grand juries should be abolished.

That's my $0.02 of thoughts on the matter...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)