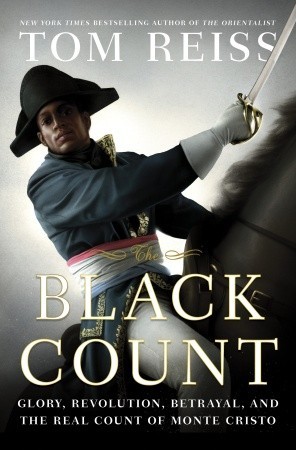

The Black Count tells the story of Alex Dumas, father of Alexandre Dumas the novelist (and grandfather of Alexandre Dumas the playwright). He is the forgotten Dumas. In France, they call his son "Alexandre Dumas, pere" and his grandson "Alexandre Dumas, fils" and hardly anyone anywhere recalls the man who first created the name and launched the legacy. Until this book was published, Alex Dumas had more or less disappeared from public consciousness, despite achievements and adventures that inspired much of his son's most successful literary output.

Alex Dumas was the son of a French nobleman and a slave woman, born on a Caribbean sugar island. His father was not the hard-working, entrepreneurial kind, but a freeloader living on his own parents' purse, then his brother's, ultimately being driven away after several years of making a nuisance of himself. When, years later, his father returned to France to reclaim an inheritance that had passed to others (as he was assumed dead after his expulsion & flight), he sold Alex Dumas into slavery in order to finance his own journey. "Sold" is perhaps a strong term. More like "pawned" - Alex was brought to France some months later and reclaimed / the pawning fee was paid off. Even so. He was pawned into slavery so his father could afford passage across the oceans. This speaks volumes of his father's nurturing attitude. (He was the favourite son. His brothers and sisters were sold into slavery outright, if my memory serves me right: it's been a month since I read the book)

From such an inauspicious background, he developed into a swashbuckling hero, a formidable warrior, a general who would lead entire armies, and a major figure on the military side of the French Revolution. He managed to achieve tasks where others failed and even got through the Terrors (the phase of the revolution when so many lost their heads as a result of witch hunts and paranoia about traitors), despite the fact that he was black and despite the fact that early in his career, he had been at interventions where the army - including himself - suppressed revolutionary riots.

He achieved all that despite being black, in Western Europe, at a time when black people were not even considered real human beings in the Christian-run empires and nations. He wasn't entirely without advantage: his father's wealth afforded him a good start in society in Paris before he abandoned all that to join the army. To his credit, he did join the army at the bottom and worked his way up through merit. As the son of a noble, he could have started at an officer's rank.

Ultimately, his career (and life) was cut short not through any personal failure, but as a result of his success: he was more impressive than Napoleon, and Napoleon could not stand him.

The Black Count is the story of Alex Dumas, but it is also the story of a tumultous time in French and European history. In fact, while Dumas' impressive achievements will probably stay a nice little anecdote in my memory, it is the book's progress through a time when solid history turned into quicksand, when ideas and notions and idealism and paranoia got to briefly rule the world, that will stay in my memory longer. That sense of instability resonates all the more strongly when looking at the Arab Spring and its aftermath. Compared to those two revolutions, the fall of the Soviet Empire seems strangely orderly, and the slow rise of Naputinon almost benign in scope. Revolutions, it turns out, tend to lead to years and sometimes decades of uncertainty and hard, messy work, before things settle into some kind of stability.

Napoleon, meanwhile, comes across as a complete weasel in this book. I had not really encountered this Anglocentric perspective in lengthy fiction before. Oh, I know, he tends to be a figure of some ridicule in movies, but since I was taught history in Germany, the general impression of Napoleon imparted to me by school education was very different in character. This book begrudgingly talks of infuriating inconsistencies in Napoleon's legacy, with the Napoleonic code adopted through much of Western Europe mentioned as a positive side effect. Perhaps understandably, German history lessons tended to have a different emphasis, with Napoleon drawn as a flawed tyrant, but one who achieved much and left a stamp on the world that lasts to this day. (Most European nations have legal systems that are built on refinements of the ones Napoleon first put in place. Britain may be built on the Magna Carta, and America is built on the Constitution, but Europe is built on the Napoleonic code)

Aside from revolutions in general, the rights of black people and slaves are of course central to the book. It turns out that, for just a few years during the French revolution, France was perhaps the most equal place in the world in terms of the rights and opportunities afforded to black people, and Alex Dumas just happened to live and thrive in the Golden Age of opportunity. There were even attempts to abolish slavery in the colonies - though those were not acted upon by the governors over there, as the sugar industry was considered too important. Under Napoleon, racism and xenophobic policies were gradually reintroduced, until they were stricter and more prejudicial than they'd ever been. Had Alex Dumas been born a generation later, he would never have been allowed into France, no matter who his father was. Had he been ten years earlier or later, he would never have been able to achieve the things he did.

With a swashbuckling, heroic subject, I expected the book to be a little more exciting than it turned out to be. I expected more -tainment from my edutainment. However, the book's structure does not allow for the build-up of tension. Even when Alex Dumas is captured and imprisoned and deadly ill, you know he will get through this because the book starts with his death, in France, while his son is having a nightmare, and because his entire career has been outlined in broad strokes at the start. Historic faction always has to battle the problem that readers might already know how everything ended. Even so, the best historic novels manage to squeeze tension and excitement and thrills from readers. The gold standard that I use for tense historical factual novels is Nathaniel Philbrick's In The Heart Of The Sea: I fear The Black Count falls somewhat short of that: I wish it had given less away at the start and made more of the periods of uncertainty. On the educational side of things, however, it is excellent, and it has a lot of interesting knowledge to impart.

Rating: 3.5/5

Showing posts with label race. Show all posts

Showing posts with label race. Show all posts

Monday, 9 March 2015

Friday, 5 December 2014

A brief interruption for some current affairs pondering

A brief interruption for some current affairs pondering

I started this blog by copying lots of the reviews I write on Goodreads into blogger. I wanted it to be a book blog, with minimal or no other things. Reviews, reviews and nothing but reviews.

But if I'm publishing a blog anyway, sometimes the need to think aloud, or even rant, might be too hard to resist. So I guess be warned: it could happen in future.

It's happening today.

Unarmed black people being killed by police in the USA (and the police getting away with it) has been a very unhappy theme this week. It's horrible. Race has become a big issue again, and it is absolutely right that people talk and think about race, and justice.

It's also right that not everyone will have the same opinions and thoughts about everything, and I decided to do some thinking below.

The Shooting of Michael Brown

I tend to get most of my news from the BBC, so here's a summary of the testimonies and different narratives about the shooting which I read: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-30189966

Of course, the testimonies don't agree about every aspect, but there are some things that seem to be fairly incontrovertible:

- Michael Brown stole something from a convenience store, became physical with the shop owner, and left with a friend.

- The police officer drove past the two young men and told them off for walking in the street.

- Shortly thereafter, the convenience store theft was reported on the police radio, and the police officer drove back to confront the teenagers.

- A physical confrontation occurred: the police officer inside the car, Michael Brown outside, the window open.

- Accounts vary: The door was either aggressively slammed into Michael Brown or Michael Brown intentionally tried to block it from opening. There was some pulling and pushing through the open window.

- The police officer shot Michael Brown several times through the window.

- Michael Brown and his friend ran away.

- The police officer, gun drawn, pursued them.

- Michael Brown turned to face the officer.

- Here, accounts vary: he either raised his hands in surrender or started to run at the police officer.

- He was then shot several more times and died.

Protesters see a martyr in Michael Brown because they choose to believe the version of the story which claims he raised his hands and shouted "Don't shoot" and "I don't have a gun". They raise their hands and see this incident as a clear cut murder, an execution of an unarmed teenager for being black or for having dared to resist a police officer (whilst being black).

Maybe that is what happened; maybe it isn't. I don't think any trial jury would ever have come to that conclusion "beyond reasonable doubt". I certainly wouldn't come to that conclusion at that level of certainty.

But, after all, it wasn't a trial jury, but a Grand Jury that decided not to charge the police officer.

The Grand Jury

This is where this BBC story becomes useful: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-30042638

"The grand jury was deciding whether Officer Wilson should be charged with any one of four possible crimes:

It also had the option of charging the policeman with armed criminal action, if it could prove he was carrying a loaded firearm with the intent to commit a felony.

- first-degree murder (any intentional murder that is willful and premeditated with malice aforethought according to Wikipedia)

- second-degree murder (an intentional murder with malice aforethought, but is not premeditated or planned in advance according to Wikipedia)

- voluntary manslaughter (any intentional killing that involved no prior intent to kill, and which was committed under such circumstances that would "cause a reasonable person to become emotionally or mentally disturbed". Both this and second-degree murder are committed on the spot, but the two differ in the magnitude of the circumstances surrounding the crime. For example, a bar fight that results in death would ordinarily constitute second-degree murder. If that same bar fight stemmed from a discovery of infidelity, however, it may be mitigated to voluntary manslaughter. according to Wikipedia)

- or involuntary manslaughter (stems from a lack of intention to cause death but involving an intentional, or negligent, act leading to death. A drunk driving-related death is typically involuntary manslaughter according to Wikipedia)

Nine out of the 12 members of this jury would have had to vote yes to indict Officer Wilson."

So, how would I have voted?

First-degree murder: No point in charging the officer. The prosecutor would have to prove, beyond reasonable doubt, that the police officer had premeditated the killing – i.e. decided to kill the robber when turning his police car around and driving to him. He'd have to prove that the police officer slammed the door into Michael Brown as an act of aggression, not to get out, but to assault him, and the killing thereafter would have to be a pure execution. I don't think such a version of events would be provable.

Involuntary manslaughter: no point in charging: there was no lack of intention to cause death. A police officer shooting a man in the head twice is clearly intending to kill.

Where things get tricky for me as someone unfamiliar with the legal system is this second degree murder / voluntary manslaughter business. I can understand "intentional killing", but find myself totally uncertain how someone can have "malice aforethought" without it being "premeditated". To my layman's ears, that sounds like a mindboggling contradiction of terms. The notion that a bar fight is somehow less likely to cause a reasonable person to become emotionally disturbed than a declaration of infidelity – that too seems bizarre to me.

Why is there no crime for "intentional killing without malice aforethought or premeditation"? Why is this system assuming that a person either has "malice aforethought" or is "mad with passion" when killing someone on the spot? ("I'm going to take this criminal off the streets" is not exactly malice aforethought...)

Personally, I would have voted that there is a case to answer for either accusation (can jurors vote for each accusation, or do they have only one vote? If only one vote, second degree murder would narrowly win out over involuntary manslaughter in my book).

But, to play devil's advocate, could there ever have been a conviction, beyond reasonable doubt, under either?

Let's have a look at this article: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-28861630

There's a lot that didn't happen. Force continuum? Doesn't sound like it. "You would only use that weapon in a situation where you felt your life or the lives of civilians in the area were in danger." – Arguably, neither was the case, so the police officer very very obviously should not have used his firearm.

But later in the article, there are some sentences about the police training that become worth thinking about:

"When law enforcement officials do shoot, they shoot to kill."

In other words, the decision to kill Michael Brown was effectively made during that scuffle at the car door. The next paragraphs explain how "shoot to wound" would be a very bad idea, and all the training is about shooting to kill, partially in order to make it easier to aim ("aim for centre mass"), and partially to minimise gunplay and end the fight as quickly as possible.

If you train police officers that, once they fire at a suspect, they are supposed to kill them, doesn't that make it more likely that some will keep shooting until the suspect is immobile on the ground?

And then comes the corker: After a police officer shoots someone…

"In the large majority of cases, no charges are brought against the officer. That is in part because in a case of reality versus perception, the police officer gets the benefit of the doubt.

"Maybe he wasn't in danger, but if he reasonably believes he was, he would be justified in shooting," says McCoy (a professor of criminal justice)."

This is where all the testimonies come back in.

The police officer's version of events emphasises his own perceptions – that he was in danger during the scuffle by the car door, that the teenager was very strong, that the teenager was charging at him after the pursuit. Any reasonable person would argue that shooting and killing an unarmed teenager is a disproportionate response to whatever crime he may have committed, and to the resistance and scuffle that occurred. Any reasonable person would agree that a grievous wrong has been done and a tragedy occurred.

But in the context of differing testimonies, and with the way police in America are trained, and considering the police officer only needed to think he was in danger, rather than actually be in danger… I don't think I'd be able to conclude he was "guilty beyond reasonable doubt". And while that, again, is the trial jury's job, not the Grand Jury's, I can imagine members of a Grand Jury thinking along similar lines.

At a Grand Jury, no defence attorneys are present. It's just the prosecutor, the judge and the defendant, and the jury can ask questions. It happens behind closed doors in secret. If I sat on a Grand Jury, and found that the prosecutor did not convince me beyond reasonable doubt that the defendant was guilty, then why would I vote to indict? If the prosecutor can't convince a jury while there is no professional defence present, what would be the point of indicting – the following trial would be sure to fail, end in a "not guilty beyond reasonable doubt" verdict, and waste huge amounts of money.

A lot would ultimately rest on that question: how convincing was the prosecutor, behind closed doors?

It is quite possible that the prosecutor only put in a token effort. [Edited, on 18/12/14: It now looks as if the prosecutor didn't just make a token effort, but went out of his way to present the defendant's case, rather than the prosecuting case, to a point where he included a discredited, white supremacist / fantasist among witnesses. I find myself completely and utterly disgusted and appalled.] It is quite possible that, with nine white jurors and three black ones, inherent racial bias is the reason why they did not indict the police officer. It's even possible that the majority of jurors did vote to indict, but not enough (9/12) to succeed.

Still, without knowing how things played out inside that room, I can imagine scenarios where I would have voted not to indict, even though I absolutely believe that the shooting of Michael Brown was wrong, and not just wrong, but a wrongful act, and very probably a crime, based on the evidence that is in the public domain. I don't believe so beyond reasonable doubt (based on the public domain evidence), and I imagine some of the jurors must be feeling pretty awful about the aftermath. I don't know that they did anything wrong by not indicting that police officer, so I don't feel I can protest about their decision.

(Protesting against police training ideologies and brutality, or for body cameras, however, and I'll happily attend)

The Death of Eric Garner

Compared to the shooting of Michael Brown, the death of Eric Garner has a lot more evidence available, thanks to this video:

Based on the definitions of different crimes earlier in this post, it seems very obvious that what is happening is an involuntary manslaughter.

Of course, the "reasonable doubt" question would arise again – and the fact that Eric Garner was overweight and unhealthy would be exploited by any defence lawyer, and is even being put forward as cause of death by a Republican politician. (Never mind that the coroner ruled it was a homicide: we are conditioned to believe that "fat people die young, of heart attacks", so if a young fat person dies of heart failure, some people will cheerfully disregard the choke hold, the handcuffs, the restraints, and blame the victim's lifestyle exclusively, or at least "reasonably doubt" that the police actions were the cause of death)

Even though I firmly believe that an involuntary manslaughter occurred, I can imagine a jury coming to a "not guilty" verdict because of "reasonable doubts". Therefore, even in this case, I can imagine reasonable people on a Grand Jury choosing not to indict the police officer (although I find it more galling than in the Michael Brown case).

Another thing which is going through my mind is that, in the video, Eric Garner is being restrained a surrounded by half a dozen police officers. Yes, one applied a banned choke hold and then pushed his head against a wall, and that is clearly disgusting. But all the police officers kept him restrained, they all ignored his pleading. They all let him die.

Eric Garner was the victim of an involuntary manslaughter, but the perpetrator was not one police officer; it was all of those present.

(If there's one positive thing about this tragedy that is being revealed about America is that there, citizens can record police actions. In Britain, the guy holding the camera would be arrested immediately and his camera confiscated: they don't let people take photos of, or film, police actions over here)

But was it an avoidable involuntary manslaughter?

Once, I witnessed someone being arrested against his will in Cardiff. The man resisted. The police applied similar levels of force to those in the video. The man started shouting "I can't breathe". The police ignored him. All the bystanders walked past (including myself), no one recorded it. My overwhelming impression was that the police are used to people shouting "I can't breathe" when being forcibly restrained.

There are several possible reasons. Maybe some people lie and shout this as a final form of resistance, or to induce others to record the arrest with a view to using it in their defence or for lawsuits. That would be the most cynical interpretation. Maybe restraining someone against their will is a highly stressful situation: maybe people being arrested in this way frequently suffer panic attacks in the process. Maybe some of the force during the arrest tends to shock the solar plexus and induce cramps in chest muscles, leading to breathing difficulties. The latter two scenarios don't tend to be lethal for healthy strong people if they happen (though they are very traumatic). Maybe it's a combination of these.

My point is: I suspect that police officers are very very used to ignoring pleas of "I can't breathe". I suspect that many police officers routinely assume that all the people who shout "I can't breathe" are lying (the first of the three scenarios I speculated about). That means that it becomes inevitable that some people die while being restrained – because the police probably always ignore it, and they always ignore it because someone, somewhere decided that they can't ever treat it as a medical emergency, or it would be open to exploitation. So it may have been an unavoidable involuntary manslaughter. It's certainly not the first time a black man has agonisingly choked to death, surrounded by witnesses, while being restrained by security ‘professionals'. (That UK case did not result in any prosecution either)

None of this makes what happened to Eric Garner right, or even remotely acceptable. But I can understand that even a non-racist jury of reasonable and decent people could come to a "not guilty" verdict, or even a refusal to indict. I find it harder to stomach than in the Michael Brown case, but I can imagine decent people coming to the decisions that both the Grand Juries reached; I cannot know for certain that either jury was made up of decent people, they may have included despicable ones. But I can imagine it, and so I choose not to direct my anger at the juries.

However.

I think the real villain of these cases aren't (necessarily) the jurors, but the systems and policies and practices that are in place in American policing & judiciary.

- Eric Garner clearly posed no danger to anyone. If he has committed an offence (and it is not clear that he has), then nothing about the offence he's accused of warranted a non-consensual, physically violent arrest.

- I believe (non-consensual) arrests should only happen if there is a threat of serious further crimes, a threat of escape after a serious crime, or at the end of an investigation leading to an arrest warrant. Police should not be allowed to arrest people willy-nilly based on nothing but their own testimony, as the police are no more worthy of the public's trust than civilians.

- Michael Brown did not pose a lethal danger to anyone. He was a criminal, there was a cause for arrest (risk of flight and risk of further serious crimes), but he was unarmed.

- Police training should therefore only be allowed the use of firearms if the suspects have a weapon – a firearm or, if they are closer, a knife or baseball bat etc.

- The definition of voluntary manslaughter should explicitly include "lethal defence of self or property against a person posing a non-lethal threat". It's simply ridiculous that white people get to shoot unarmed black people, claim "self defence" and too often get a "not guilty" verdict or no indictment. There has to be a proportionality to any claim of "defence", and there have been too many instances of people using lethal violence in instances that do not warrant it. (lethal self defence against rape is OK in my book, but lethal self defence against a petty thief or someone resisting against being arrested against their will… there should be a defined crime for that!).

- I don't live in America. Those that do, tell me that "race" is still a big issue, that institutionalised racism is still widespread, and I believe that, even if I can't know for certain that it was the deciding factor in either of the cases that have triggered these protests and responses.

- From over here, across the pond, it looks as if one of the biggest reasons for the too-frequent killings of unarmed suspects is that American ideology values (defence of) property over lives. (Police would rather shoot a petty thief than let him escape unpunished, once they have started the chase). Police forces value their need to enforce a decision once made over lives. (It is more important to them to go through with an arrest, once they announced they're arresting someone, than preserving the life of the suspect). If the individual police officers in these cases are not "guilty beyond reasonable doubt" of involuntary manslaughter, then the police forces themselves, their training methods, policies and ideologies are, in my opinion, "guilty beyond reasonable doubt" of fostering a culture that leads to involuntary manslaughters - i.e. the authorities themselves should be prosecuted for corporate manslaughter.

- Grand Juries seem a strange idea. The decision whether to indict or not should be made by a professional, identifiable and accountable person. (A judge, magistrate or whatever). And if a Grand Jury has to be involved, why a 9/12 majority rather than a simple majority? Members of the jury should probably not just include peers of the accused, but also peers of the victim…

- ideally, grand juries should be abolished.

That's my $0.02 of thoughts on the matter...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)